The Productivity Commission (PC)’s new interim report on education and the performance of our systems as a result of additional funding has again demonstrated just how poorly public education is faring in resource allocation.

The PC’s chart on school funding between 2011 and 2020 shows that public schools have enjoyed only a modest real increase in funding over the decade, compared to substantial increases in real funding for Catholic and independent schools. Catholic school funding per student has now overtaken that of public schools, and independent schools have dramatically increased funding per student to levels far above that of public schools.

The disparity was primarily driven by big increases in Commonwealth funding for Catholic and independent schools, while other funding sources, including state government funding, stayed broadly the same. While public schools had only a relatively small increase in Commonwealth funding, both Catholic and independent schools were given substantially greater Commonwealth funding.

Bear in mind this is funding per student, not overall levels of funding — the public sector is much larger than the Catholic or independent sectors.

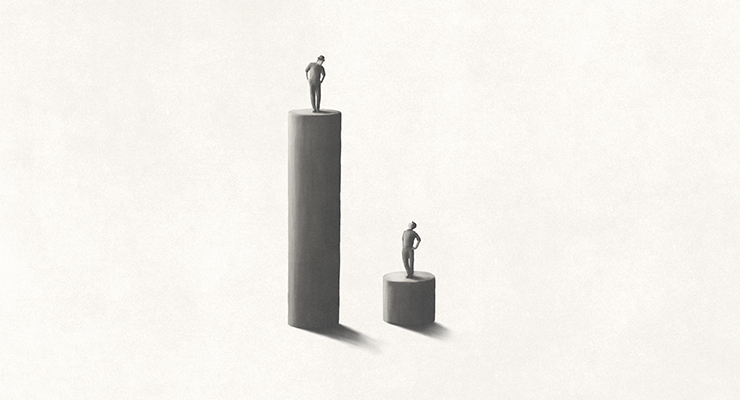

As the PC notes in its report, “investment in education has been found to reduce inequality”. But when investment flows to already wealthy schools, or flows disproportionately to one sector so that its resourcing grows much faster than the public sector, it has the opposite effect: entrenching advantage for those able to afford Catholic or independent schools. The PC suggests that this may be an important reason why “overall, gross school income per student has increased by nearly 20% in real terms since 2011, with little discernible improvement in test scores” — much of that increase has not gone to where it is needed.

That’s one key sector where government policies are entrenching inequality, but it is by no means the only one.

As Brendan Coates of the Grattan Institute recently explained in his excellent speech on housing, “The Great Australian Nightmare“, while income inequality in Australia hasn’t been growing markedly worse recently, housing policy is ensuring that wealth inequality has: “if we consider incomes after accounting for housing costs, inequality is growing, with the poor being hurt the most”.

As Coates points out: “the growing divide between the housing ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ also risks being entrenched as wealth is passed onto the next generation … Big inheritances boost the jackpot from the birth lottery. Richer parents tend to have richer children. Among those who received an inheritance over the past decade, the wealthiest 20% received on average three times as much as the poorest 20%.” Home-ownership has fallen substantially among low-income earners since 1981.

This too is the result of government policies: negative gearing and capital gains tax settings, poor housing development approval processes, and a lack of social housing investment.

We’re also entrenching inequality on wages growth. As a Reserve Bank paper from 2019 showed, the great wage stagnation of the Coalition years disproportionately hit lower-income earners.

The highest income earners had the highest wages growth from 2009-17, and the lowest wage earners had the lowest growth. And while wages growth slowed in the 2010s, it slowed much faster for low-income earners (down 2.71 percentage points) than for high-income earners (down 2 points). It also slowed more for people with lower education levels and low-skilled occupations.

Despite the best efforts of the Reserve Bank to pretend that wages growth is improving, wage stagnation remains entrenched in the Australian economy in the wake of the pandemic — in fact, the RBA seems now to be counting on workers lacking the capacity to increase wages growth in its fight against inflation.

And this too is a deliberate policy of the previous government, in an industrial relations system tilted heavily against the bargaining power of workers in which trade unions were specifically targeted with legal harassment by regulators with extraordinary powers, while temporary migration was used to suppress wages.

Unlike in housing and education, the new government appears committed to tilting the balance back in favour of workers, especially through allowing industry or multi-employer bargaining, and the abolition of the discredited Building and Construction Commission. Labor has been willing to take on employers in the interests of its key donors, trade unions, and the interests they represent, workers.

But in housing and education, we continue to allow powerful interests — homeowners and housing investors, wealthy seniors, the property industry, the Catholic Church and wealthy private schools — to dictate policies that reward the wealthy at the expense of taxpayers. Indeed, in the Malcolm Turnbull years, Labor actually aligned with the Catholic and independent school sectors to oppose an attempt to reduce funding for wealthy private schools.

The result is an ongoing entrenchment of privilege and perpetuation of inequality — a country where winning the birth lottery is crucial.

Are you affected by rising inequality in Australia? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Ontario has the model of schools only receiving subsidies if they are fee-free. As a result, there is a strong Catholic sector there, which has helped to preserve Irish and then Caribbean / Latin American identities linked to faith. This is also happening in places like Wadeye and the Tiwi Islands, where the Catholic Church has managed to help preserve language and identity where government has failed.

The argument that Churchie, Shore, the many PLCs of the world need any subsidies doesn’t wash, let alone tax-deductible status. As a former student of an independent school myself, it took me a long time to realise what Australian schooling was like, and the social impact of the stratification of society through private and public schools. This is an anathema to the egalitarian ideal of Australia, and has given us much of the bastardy we are seeing in our ruling class and leading voices today, and corresponding lack of innovation and efficiency throughout much of society through stratified education that puts wealth before knowledge.

MY wife went to school in Ontario. She could not believe that we funded private schools when she arrived in Oz.

One-third of students go to non-government schools, the vast majority of which are in low fee schools. They receive government funding because it’s a good deal for taxpayers.

There are 4 million students in Australia and every one of them has to be educated. It costs about $15,000 a year to educate a child with no disadvantage. If parents pay some of that cost for one-third of all students, that’s 1.35 million students taxpayers don’t have to fully fund. Public schools receive $7,000 per student more than non-government schools each year (according to the Productivity Commission, it’s $20,182 v $13,189).

Is that you Kevin Donnelly?

Sprung again!

I cannot understand why private/religious schools are not required to open their books to scrutiny before they receive any government funding.

When I was competing in pro running I ran a couple of times at Trinity Grammar in Melbourne. The oval was like a bowling green and there were 11 turf practice wickets! I doubt any of the District Cricket clubs in Melbourne could boast that many.

I had a few state turf cricket net sessions at a private SA school. Never Have I seen such perfect amenities in grade cricket.

I can’t help thinking about the similarities between our private school system and gun control in the States. Regimes founded in long gone era for circumstances relevant to their times but kept alive by conservatives unwilling to move with the times. Their numbers a minority but still large enough to frighten the hell out of any political party willing to question what they believe are their historical rights.

The biggest problem this political lobby poses is that we never hear an election debate or see an election fought on what is the most important issue facing our nation.

Steven, they have to lodge detailed financial statements on all their private and public income annually to the federal Dept of Education.

A summary of every school’s finances appears on the MySchool website.

No doubt constructed by innovative financial wizards, possibly with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo

hear hear!

Agree, reduce funding for the privates and boost funding fir the pubkic schools. If I had my way there would be no private schools, religious, ethnic or otherwise.

There will be no changes to the housing laws since nearly all of our pollies have their heads in the trough as landlords.

Nailed it, Mr Smith. You might also want to erase much of the Air B&B rort, restrict investment properties, and grant the poor bloody renters (those who aren’t homeless) some real advocacy. Oh, in my dreams…

… and those “pollies with their heads in the trough as landlords” get to vote on the housing laws.

What is wrong with this picture?

They also decide if tax cuts that they will benefit from handsomely go ahead…

Simple eh.

OMG NO. competition is so important. If government schools were all great then I might agree. But, curriculum, teaching methods, and beauracracy all contribute to making schooling quite awful for both teacher and student.

Statistically it is clear that overfunding private schools produces worse outcomes. You can almost 100% correlate the big increase in this with the long decline in outcomes, beginning with Howard’s massive rigging of the socioeconomic status models. Even now, it is almost impossible for a private school to lose funding, no matter how well off or how lopsided the numbers.

More importantly almost no public school in the land is properly funded. I work in a fairly low SES rural school. We spend a fortune on student welfare, medical interventions, hearing and vision screening, language pathology. We have a number of families with parents incarcerated, with drug related issues, domestic violence and just lousy circumstances. We get one day of counsellor time a week. We desperately need speech pathologists, but we need to go online for that at considerable cost and it just ain’t the same.

When I started working here, we worried about kids who could not say the alphabet in kindergarten and perhaps write their name. Now we worry if they can’t say their name.

Far out, that’s disconcerting…

My loathing of Howard is boundless. The Rodent was our Thatcher; utterly vandalised the nation.

Thank you, Keane. I’ve long said that we are hurtling back to being a feudal society ruled by wealth, where the poor will be regarded as little better than animals. This only confirms it. Love to know what the hell we can do about it.

I’ve been saying for a decade we are back in the late 19th century. Work/wages, health and housing. This time we don’t have the Labor party in parliament looking out for those who are struggling in life.

Never vote liberal again…

Unfortunately Labor is committed to the (over)funding of private schools, propping up private health insurance, the privatised system of employment services, the inadequate benefits that condemn people to going hungry and not getting proper medical care etc. And their plans for the delivery of affordable housing are ridiculously inadequate.

But other than those things, on the side of the battler?

At this stage only vote Independents is where I’m at 🙂

Where do they sit on the stage 3 cuts?

Sucking their thumbs.

What do you mean, *ever* vote Liberal? How can anyone with a clue fail to recognise the Lying Nasty Party?

And, as agatek says below, anyone expecting better than LNP lite from Labor these days is whistling in the dark like a mug.

They should never be called ‘independent” schools. They are nothing of the sort. They are heavily subsidised schools. Taxpayers pay the subsidy. So taxpayers subsidised schools is the proper term.

The same applied to private medical insurance – the rebate thus wasted would be better spent on the public system.

Then we could tax the property portfolios of the religion industry, which rivals gambling in being utterly deleterious to society.