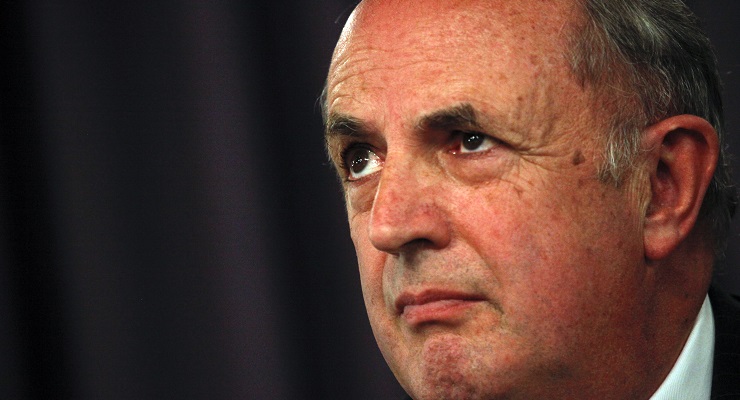

The way the left will tell it, Peter Reith’s story is one of failure and scandal: John Hewson’s deputy in the ill-fated Fightback program; the architect of the 1998 waterfront dispute, which included the notorious attempt to train mercenaries on the docks of Dubai (of which Reith denied any knowledge); the children overboard lie; the phone card scandal that finished off his political career.

Six years in London at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development followed before he returned to Australia and re-engagement in politics within the Liberal Party — one hampered by serious illness. His attempt to become Liberal Party president in 2011 was dudded by Tony Abbott, the then opposition leader having encouraged him to run but who switched his vote at the last minute to Alan Stockdale, who defeated Reith by one vote. An unhappy Reith then lashed out at Abbott in an op-ed that also attacked Abbott’s lack of interest in industrial relations reform.

That stung Abbott — who kept insisting WorkChoices was dead — to say he and Reith stood “shoulder to shoulder” on IR. “I should lose elections more often,” Reith sourly responded.

Reith never lost his enthusiasm for politics. I joined him in Albury in the 2010 election, where he was helping Sussan Ley — who is now one of his successors as Liberal deputy. It was fascinating to watch him walk into a breakfast debate of all the Farrer candidates — the kind of run-of-the-mill political event that no one but the local paper bothers to cover — and head immediately to the other candidates and talk to them, as if he couldn’t resist engaging with even the lowliest, most unlikely political soldier. They were people who had put their hands up for political battle, whether he agreed with them or not, and he wanted to know about them.

But as the spat with Abbott showed, he never lost his passion for industrial relations “reform”. For Reith, the point of politics wasn’t merely to oppose what the other side was doing but to deliver positive reform. The spirit of Fightback — a comprehensive program of hardline economic reform that became a huge target on the backs of Liberals in 1993 — lived on in Reith. He had entered Parliament at the tail end of the Fraser years, and as deputy leader bluntly declared them to be a wasted opportunity. Fraser had failed to reform the Australian economy, he said, and the Liberals must not make the same mistake once elected.

He repeated that after he lost in 2011: “The Liberals must win the next election but winning is not enough. Let’s aim higher than a rerun of the Fraser years.”

Reith’s problem was that the Fraser years had delivered any number of major reforms and achievements, but not delivered the kind of economic revolution he thought Australia needed.

Abbott turned out to be worse than Fraser by orders of magnitude. And he provided harsh evidence that Reith was correct: a party that was the reverse of Fightback, one capable only of opposing and not of articulating its own program, was also doomed.

For Reith, power was to be used creatively, not just to block. Whether a new generation of Liberals will absorb that lesson is yet to be seen.

Look Bernard, it does not look or bode well to speak ill of the dead but do you know what you are saying? This is Peter Reith, Minister for Industrial Relations who introduced the 1996 Workplace Relations Act which made public servants the equivalent of building sub-contractors in the eyes of the law, was an architect of Fightback, with all its pro-GST, flat tax, flat earth palaver spiced with threats to social security recipients, was a minister for Defence, who lied about asylum seekers throwing their children overboard (from a leaking vessel) then failed to correct the record, put thugs and dogs on our waterfront in an industrial dispute – this guy like all conservatives, didn’t see a working person who he didn’t want to kick and take his money.

He resigned from politics in 2001 and one wonder what damage he would have done to the Australian community had he served the full length of the Howard term.

Even after he left parliament he took a “job” with a Defence based public relations firm after having served as Defence Minister for nearly 2 years. Lining his pockets further. Similar to former Health Minister Michel Wooldridge. And Andrew (be kind to me) Robb. Came to prominence after winning the seat of Flinders in the 1982 by-election which Labor were expected to win. This result saw the end of Bill Hayden as ALP Leader and was the slow burning catalyst for the rise of Hawke to ALP Leader and eventually PM. Won the seat after another useless Liberal (what Liberal isn’t useless?) Phil (kidney stones) lynch retired from politics after having done nothing about Employment, Inflation, Unemployment, Economic Growth, Economic Reform and presiding over a period of shadow banking, shonky financial trading and government economic ineptitude in the, correctly stated, long lost last years of the dreadful Fraser administration. Only Morrison’s was worse.

Like Howard they should have pursued law, business or, heaven forbid, cricket.

A funny anecdote: back in the 60’s when I was at ARDU at RAAF Laverton, we heard of a P. Lynch who was joining the RAAF reserve (weekend warriors) with the rank of pilot officer. Then we heard that he declined to join after getting a better offer…Liberal party minister.

Ha! Good one. That’s why you’re alive today.

Actually I tried to do the same myself. I cannot lie to myself or the readers here but in 1999 I tried to join the RAAF Reserve while working full time in the Public Service. Starting rank I think was Flying Officer. I missed the cut but it may have been a blessing in disguise as many things are. It’s just I live near a RAAF Base and it would have been convenient and I would get 2 pays. I didn’t become Treasurer either!

Damn straight. Had to check to see if I was accidentally reading a Madonna King article

Your opening sentences lay out his appalling record, nice bit of concessive work on your part, and then move on to say what a great guy he was? Say what? And who is this “left” you speak of? Do you need to be “left” to have complete disdain for his work in manufacturing the waterfront dispute? That he used the apparatus of the state like a tin pot dictator, to lock out an entire workforce? How’s those “balaclavered” thugs looking now? I went down to the Hungry Mile during the lock out, in my suit and tie by the way Bernard, and was part of a a crowd that represented every aspect of modern Australia, people who were just outraged by Reith’s work, Howard’s connivance and what it meant for us as a nation. Reith laid the platform for so much of what came with Abbott et al and as a public figure he is to be despised and his legacy traduced. I wish no ill to his family who are suffering a loss, but as a public figure he was a hugely problematic figure with a very dark legacy. This trite approach you have taken is very, I repeat, very disappointing.

Australia needs more Liberals like Reith like a hole in the head.

I look forward to the Rodent joining Reith in whatever form of afterlife lying conservative political rogues suffer.

Should have gone about 20 years ago after the lying rodent had departed, but that’s life

IKR. Saw a bloke in the supermarket a few years ago rocking a shirt saying STILL HATE THATCHER – that was proper.

These villains give no quarter, so failing to respond in kind is suicidal.

In 1988 four sensible and reasonable propositions were put to referendum. They were agreed by the normal process of constitutional convention and the relevant enabling legislation was not opposed by the LNP – who I understand initially agreed to support them. These proposals were for:

None of these proposals could be considered remotely controversial and all of them would have improved our political and legal operating systems.

It was Peter Reith who argued to Howard that to support them would give the Hawke government a victory, so the LNP decided to actively oppose – for no other reason than their perception of their short-term political interest.

This was the man who put personal interest ahead of the public interest he had sworn to serve.

This is the man whose reputation Bernard has decided to try and restore.

Yes- let’s be honest! Peter Reith was a nasty, lying, hypocritical bastard, who achieved nothing of any significance. Just a typical R Wing Liberal!!!

Bernard went off-piste here

and I don’t mean want he represented but how represented

Silence works

Reith will be remembered for conspiring against Australian workers and lying to the public in his attempt to demonize desperate refugees for political advantage. Nothing else – zero, nada.

Peter Reith used his power ‘creatively’?

As in jailed accountants work ‘creatively’?

Fudging the figures, lying, omitting important information, misusing funds that don’t belong to them, misleading their clients, etc, etc.

That kind of ‘creative’?

This is the man who used legitimate asylum seekers as fodder for his own and his boss Little Johnny’s ambitions, who blamed everyone else for his deception, who brought attack dogs onto the waterfront to cow legally enrolled union members, then employed non-Australian mercenaries to do workers’ jobs, and who laughed about it all with his big business buddy Chris Corrigan.

Yup. A beloved political figure who definitely contributed to the betterment of Australian lives by legitimising cronyism and political trickery while undermining the rule of law.

He and Howard are the grandfathers of everything that’s rotten in Australian politics today.

Well done, good and faithful servant.

Well, and Fraser too…probably the most hated of the three in a tight contest, with Abbott and Morrison hot on their heels as rotten political history unfolds.

All worthy of their places in the Coalition Museum of Infamy