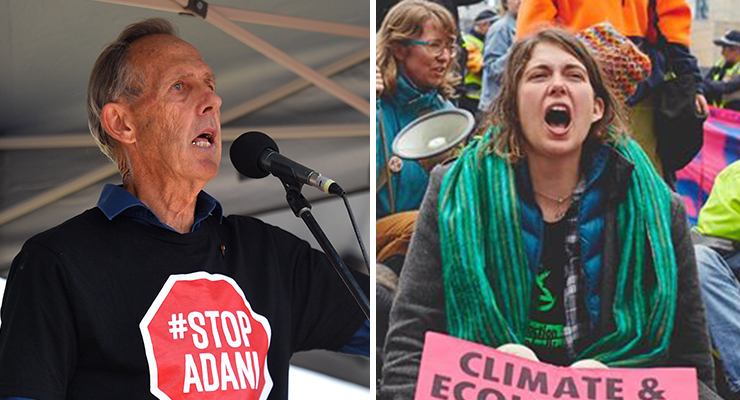

“After the High Court’s decision on the Franklin River on 1 July 1983,” said Bob Brown to Crikey, referring to the famous Tasmanian dam case during which he was arrested, “I stated we had entered a new era of environmentalism and that it would never be so hard as it was in the Franklin campaign.”

“I was totally wrong.”

Nearly 40 years on since the historic victory — in which the Commonwealth government succeeded in stopping the large hydroelectric Franklin Dam being built in Tasmania — the founder and former leader of the Greens was once again arrested, but this time under newly introduced laws that carry $13,000 fines or two years’ imprisonment for protests on a forestry site. The same laws also impose $45,000 fines on organisations, such as the Bob Brown Foundation, which lend support to such protests.

Far from heralding a new dawn for environmental justice, Brown said, the Franklin campaign had proved something of an aberration.

“We now have a situation across Australia where environmentalists are jailed and environmental exploiters are protected and subsidised,” he said of his arrest a few weeks ago.

“Instead of increasing environmental protection, we have laws that do the reverse — laws which foster the self-made environmental tragedy of this planet.”

Brown is yet to face court, and so it remains anyone’s guess whether he’ll meet a similar fate as that of Sydney environmental activist Deanna “Violet” Coco, who was sentenced to jail last Friday. To his mind, it’s a moot point.

Criminalising climate activism

The larger and more pressing dilemma, Brown said, — and one which belongs to the current age — is the growing tendency of government to criminalise peaceful protest, while climate breakdown and mass extinction envelop the world, forever sealing its fate.

In August, Victoria’s opposition united with the Andrews government to pass laws comparable to Tasmania’s, running roughshod over a chorus of concerns voiced by civil liberties groups, unions and environmentalists.

Three years earlier, in 2019, the Queensland government rushed through sweeping limits on the right to protest, underpinned by unsubstantiated claims of “extremist” conduct by environmentalists. The resulting legislation expanded police search powers and criminalised “dangerous locking devices” — such as superglue or anything activists might use to secure themselves to pavement or buildings — as a means to silence dissent.

And in New South Wales, concerns about traffic disruption were similarly seized upon following climate protests in Sydney and Port Botany earlier this year to hurry the introduction of two-year jail terms and $22,000 fines for “illegal protests”.

The laws, which criminalise “illegal protests” on rail lines, bridges, tunnels and — most contentiously — public roads, were passed within two days with the unqualified support of the Labor opposition mere weeks after the government flagged a crackdown on environmentalists.

Though seemingly aimed at “anarchist protesters”, as NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman put it, the breadth of the provisions suggests otherwise.

“Because the provisions are so loosely drafted, so imprecise, the laws can apply to almost any situation of people being on a road,” said Coco’s lawyer, Mark Davis.

“The Roads Minister Natalie Ward didn’t know herself if ‘public road’ meant ‘major road’ or any and every road. It’s a disgrace. It gives police an unlimited, utterly arbitrary discretion to arrest anyone on a road protesting about anything, not just climate.

“Short of some prominent dictatorships, we are world leaders with this kind of legislation. And the courts, or at least one court, has shown us the gun is loaded and they’re willing to fire it.”

Disruption and democracy

Against the backdrop of this legislation, now the subject of constitutional challenge, environmental demonstrators across Australia have regularly been denied bail or otherwise forced to contend with disproportionate bail conditions, while those residing in New South Wales have had espionage activities undertaken against them by a new police unit, Strike Force Guard.

In a statement to Crikey on Wednesday, New South Wales Deputy Premier and Minister for Police Paul Toole defended the laws.

“Illegal protests that disrupt everyday life, whether it’s transport networks, freight chains, production lines or commuters trying to get to work or school, will not be tolerated,” he said.

It was a sentiment shared by Premier Dominic Perrottet, who days earlier labelled Coco’s 15-month prison sentence “pleasing to see”, adding “if protesters want to put our way of life at risk, then they should have the book thrown at them”.

In answer, the famous physicist and climate scientist Bill Hare said, via Twitter, that the inconvenience occasioned by “protest is not comparable to [the] catastrophic risk to [the] environment and serious damage to our way of life caused by fossil fuel emissions”.

Hare — the lead author for the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, for which the IPCC was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize — added that Perrottet’s statement was one of the “most regressive, anti-democratic statements” he could recall in Australia “for a long time”.

It’s a view which throws the shifting definition of what is deemed lawful dissent into sharp relief, Ray Yoshida of the Australian Democracy Network told Crikey.

“It’s doublespeak for the NSW government to say they support protests as long as they don’t break the law, and then pass new laws that shrink the space for people to act,” he said.

“The jailing of peaceful protesters is chilling for anyone who cares about our democracy — we need to restore and protect the right to protest before it’s too late.”

Had such laws existed at the time of many of Australia’s historic environmental wins — from the Franklin River to the Kakadu and Jabiluka blockades — many, perhaps all, would have met with failure.

“There’s no doubt these laws would certainly have had an adverse impact on bringing to the public’s attention the Franklin Dam issue and, for that matter, a range of issues that have been brought to prominence in the public’s mind because of protests,” Greg Barns SC of the Australian Lawyers Alliance said.

He added people too often overlooked the hundreds of arrests which occurred during the Franklin River campaign, but under ordinary trespass laws that impose lesser penalties.

“The reason [the new laws] are unnecessary is because there are already ample laws on the statute books, such as laws relating to trespass, criminal damage, that deal with these types of situations if people break the law,” he said.

“What [Coco’s] sentence shows is that these new laws are draconian. Her sentence is a draconian penalty allowed for by a draconian law.”

Why now?

Given ours is the age of looming, if not inevitable, climate disaster, all of this poses the inevitable question: why the crackdown on environmentalists?

In Brown’s view, it’s no accident of history the techniques used by campaigners in the past are being targeted by government. It’s a phenomenon, he said, which conversely owes its existence to “state capture” by the fossil fuel and logging industries.

“The extractive industries, who want to convert nature into profits, can no longer win the argument with the public on the environment, so they have to ‘take out’ the environmentalists,” he said.

“These laws are meant to kill environmental activism and frighten people into silence.”

In this connection, there’s little denying climate anxiety, and concomitant calls for climate action pose a risk to such corporations.

A recent analysis of World Bank data undertaken by Belgian energy and environmental economist Aviel Verbruggen, a former lead author of an IPCC report, found the oil and gas industry had delivered more than $4 billion in profit every day for the past 50 years.

Following the report’s release, Verbruggen said: “You can buy every politician, every system with all this money, and I think this happened here. It protects [polluters] from political interference that may limit their activities.”

While Brown doesn’t believe any Australian politicians have been bribed or “bought”, so to speak, he said the lobbying power of the industry was obvious, both on a domestic and global level.

“By and large, [our politicians] are just suborned by this lobbying tour de force, which is not being matched by the non-governmental sector, which is the guardian of the environment,” he said.

“The striking similarity between Australian [anti-protest] legislation and the UK’s legislation is a clue which indicates we’ve got a global corporate governance.”

To buttress this view, Brown pointed to the $700 billion in taxpayer subsidies received by oil and gas companies globally in 2021.

Viewed in this context, he said, the anti-protest laws were self-evidently designed to shatter the unity underpinning the rise of collective, society-wide pressure to move on climate action.

Environmental Justice Australia ecosystems lawyer Natalie Hogan agreed the laws were a “politically motivated crackdown on legitimate political expression”, and ones that illustrated the efficacy of environmental campaigns.

“These protests provide very important community oversight,” she said in reference to the illegal logging in Victorian forests exposed by environmental demonstrators and citizen science groups in recent years.

“It seems very inconsistent to [tell Victorians] native logging will end by 2030, and then introduce laws that disproportionately criminalise or penalise people engaged in legitimate protests or citizen science in forests.”

Others, however, believe the anti-protest laws represent yet another skirmish on the law-and-order politics theme.

“Banging the law-and-order drum has been fashionable for over 20 years,” Greg Barns said. “I think that’s the issue at play here — it just so happens to be climate change in this instance.”

“The irony is that it will probably have the impact of emboldening protesters to take more extreme action because they see the laws as unjust.”

The future of protests

Not everyone has cast doubt on the deterrent effect of the laws, though. Coco’s lawyer Davis said the laws — which he defined as a “knee-jerk response to tabloid media” — would achieve their desired result.

“Of course it will work — who would be insane enough to organise any sort of free protest? You can go to jail for a long time. It’s nuts,” he said.

Either way, Davis added, it’s clear such laws were placing the limits of Australia’s reputation as a liberal democracy under extraordinary pressure.

“You cannot be a fully functional democracy if you cannot voice dissent to the government power,” he said. “It’s simply impossible.”

“To be on a road, to use a road, is intrinsic to the right to protest and the fact that’s now seen as somehow radical tells you about the cultural shift we’re witnessing.”

Brown, for his part, believes it would be foolish to bet on a decline in environmental protest, notwithstanding the laws, given the climate predicament confronting the globe.

“You’ll see the showdown of our age between green and greed,” he said.

“But ultimately responsibility for [change will] fall to voters. Four out of five Australians feel strongly about [the environment], yet four out of five Australians vote for the major parties. And there’s the dilemma for democracy.

“These laws will only continue to get worse if people don’t vote for the environment.”

After all, he said, dealing with global warming and the extinction crisis is, and always has been, about the balance of power.

Now that someone who carries out a peaceful protest that has any impact (invisible protests are apparently still allowed) faces the sort of penalties that result from acts of serious violence, there is no longer any deterrence to extending protests to violent action, is there? Or am I missing something?

The powers that be would probably welcome a violent protest. It’s much easier to justify unleashing the full power of the state on violent protesters, than it is on non violent protesters.

The flaw in your argument is that the ‘powers that be’ have already crossed the line and justified unleashing the power of the state on peaceful protesters. So it’s all one game now.

The powers haven’t taken any action to speak of against the violent protesters who carried on about “Freedom” and so forth during covid lockdowns.

Other than it putting people offside?

Where should the violence be directed?

Is there some sort of violence that actually stacks up as worthwhile? Asking for a friend

A trawl through history should quickly and easily provide informative examples. As John Harington said some 400 years ago,

… it is also often found that those who use political violence are only terrorists for as long as they are not winning. The nature of their politics can be anything, all that matters is coming out ahead. The esteemed and respected founders of more than a few nations around the world were for a time nothing but terrorists, seditionists and rebels.

So basically it boils down to ‘go hard or go home’ – just what I’ve been saying all millennium.

I’ve made two attempts to reply, but the ModBot is in fighting form today.

(I am getting really sick of the stupid Mod Bot.)

Dominic Perrottet claims that ‘protesters are putting our way of life at risk’. That’s interesting. I always thought that the Australian way of life revolved around civil rights, human rights, some level of egality, and justice. I must have forgotten that we were once a prison colony, and that fossil fuel-captured governments across the country are trying their best to return us to that condition.

One fundamental problem is that the Australian constitution has nothing useful to offer in protection of human and civil rights. A bill of rights embedded in the constitution would give citizens some recourse against this kind of government overreach, but the Australian Right doggedly opposes any such thing, claiming that it would only empower “activist judges”. Until we have human and civil rights codified in the constitution, governments can get away with detaining people on offshore islands indefinitely without trial and inflicting draconian gaol terms on non-violent protesters.

Maybe we could give protestors some sort of ‘Voice’ to parliament?

So many others demanding to be heard that it’ll be referenda until the the heat death of the Universe.

Over here in the Deep West, where Mark McGowan governs on behalf of Woodside and Kerry Stokes’ daily propaganda sheet celebrates the incarceration of anyone raising a voice against the extraction industry, applying chalk to the pavement is now considered a criminal act.

It sounds like a Monty Python skit. Which premier will be the first to ban books…

Or burn them.

Absolutely appalling stuff – why is it always Right wing governments that do / allow this sort of totally disproportionate action. Another nail in the LNP NSW coffin as far as I can see. May they follow their Fed counterparts into oblivion. And for Perrotet to applaud the decision makes it worse.

Dictator Dan has also passed laws to protect loggers as they strip Victoria of the last mature eucalypt forests to turn into wood chips and pulp. By 2030 none will be left. Don’t know what the loggers will do then.

Who is going to supply the raw materials for the japanese newspapers then ?

That’s a worry.

Did you miss the bit about these laws passing with the full-throated support of NSW Labor?

While I reckon the Labor Party is right of centre, you didn’t make it clear that you consider the Labor Party to be right wing.

Quite so. My omission

About 1 goosestep to the left of the Coalition.

Queensland has similar laws. So does Tasmania and Victoria and in each state the major party in opposition fully endorsed them.

The major parties deserve to have their arses handed to them, but the mug punters can’t see it… They’re waking up way too slowly.

Ahh..because 99% of decent people want these fleas dealt with

Opinions on who is “decent” differ wildly, depending on the speaker’s politics.

…and some basic grasp of those number thingies.

Deceny is environmental vandalism? I suppose from a government and industry perspective that’s accurate but every other species on this planet and future generations might disagree with that view of decency.

That might be a damning takedown of the NSW Government, were it not for the fact that Labor voted with the Coalition to pass the NSW laws.

As in federal parliament it helped pass even Draconian ‘security’ & surveillance law Scummo could think up, despite mewling platitudes beforehand..

This is a problem of both sides of politics. Which is what makes these laws so worrying. Bob Hawke would be rolling in his grave.

“always right wing governments”? Andrews has enacted draconian protest laws here in Vic as well.

I feel an uncanny sense of deja vu when I read these stories, from the days of the protests against the Vietnam war and apartheid in South Africa. Most of Crikey’s readers would probably be too young to remember NSW State Premier Askin saying “run over the bastards” to his driver when obstructed by demonstrators against the State visit of US President Johnson as the Vietnam war was being escalated. Then there were the mass arrests of demonstrators and civil liberties observers during the Springbock demonstration in the ACT. One of these was Jack Waterford (who went on to become the editor of the Canberra Times) and another observer who went on to become a very popular Federal member for northern Canberra. It would be an interesting exercise to dig up the rhetoric and the reporting of the demonstrations and demonstrators of that era, and compare it with the froth and spume of the current establishment.

The entrails of Askin’s humanity spread all over the road – as imortalised in that “Mavis Bramston” (Gordon Chater, Noeline Brown and Barry Creighton (?) – vocals) hit of the day “Run, Run, Run the Bastards Over”?

Many of my schoolmates and I, mostly aged 17 and doing our Matric year (HSC for those not of that era), nipped away from school (Melbourne High) to go into the city on a Friday afternoon in 1970 to sit with many (hundreds of) thousands of others at one of the Vietnam Moratorium protests in Swanston St, organised by Jim Cairns. A fair swathe of Melbourne’s CBD was shut down and there was nothing anyone in authority could do about it. We saw the VICPOL Special Branch and ASIO cameras trained on the crowd through the open windows of the Manchester Unity Building on the corner of Collins St, opposite the Town Hall. Good luck identifying us all, I thought, although possibly they were looking for draft dodgers.

The only way to not be arrested at demonstrations is through safety in very very large numbers. Then the media can’t portray demonstrators as radicals and instead have to start giving serious commentary about the issue that is driving them.

Alternatively, organise schoolchildren and seniors to protest – let’s see Perrottet expressing satisfaction about jailing them.