A city council declaring a concrete car park a heritage site sounds like a satire of architectural pretension. But in Melbourne, it could soon become reality.

An official review recently recommended a seven-storey car park in Carlton be covered by a heritage overlay. The report’s authors declared it “striking, robust and bold”, despite locals telling The Age they find it “pretty grey” and that it would be better used for housing. The City of Melbourne will make a final decision later this year.

I work across the road from the “Brutalist” slab and don’t find its hulking frame particularly inspiring on my lunch breaks — nor do I value the dead, expensive space it takes up, especially at a time when cities internationally are increasingly junking car parks for walkable public spaces.

The prospect of this car park being repurposed as housing is particularly appealing to local workers like me, who must fork out higher rents to live within cycling distance or traipse long distances from more affordable burbs. This is partly because Carlton is a notoriously low-rise area despite its proximity to the CBD, largely due to heritage restrictions.

Carlton is hardly the only heritage battlefield. Across town in Footscray, Maribyrnong City Council is seeking to extend a surprise interim overlay on around 900 suburban homes. And it’s not just a Melbourne problem — in Brisbane, prospective renovators in Moorooka are also fighting increased heritage restrictions.

Could relaxing heritage laws in Australia’s cities allow more homes to be built, trimming commute times while lowering rent and property prices?

A maze of heritage zones

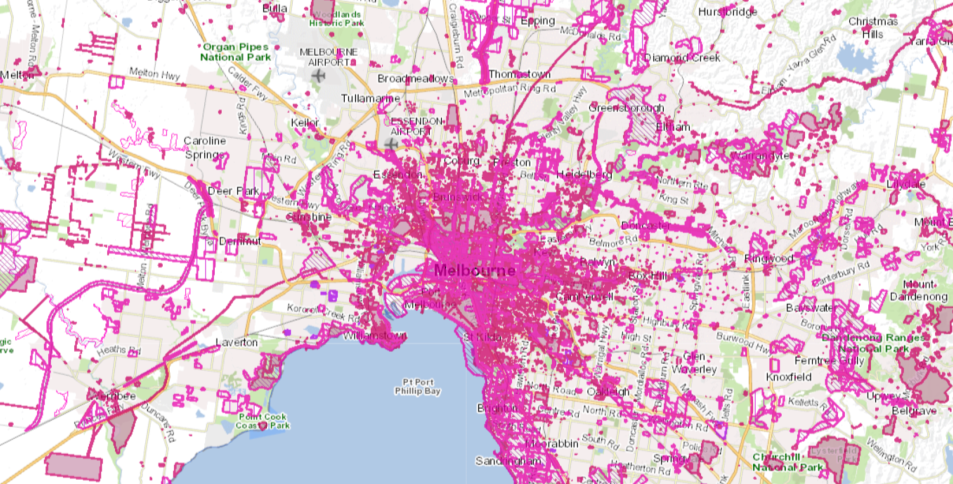

Heritage overlays now cover vast areas of our inner and middle-ring suburbs.

It’s not just overlay areas that are affected, but adjacent areas too. In East Melbourne, a nine-storey apartment block was recently knocked back because it adjoined a heritage-listed property, introducing steeper hurdles on height and design. A dilapidated office building, which The Age called “one of Melbourne’s worst eyesores”, remains standing following the local council rejecting a 77-apartment block late last year (partly due to it being a few minutes’ walk from the heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building).

Critics suggest such restrictions, often based on niche aesthetic considerations or locals’ self-interested NIMBYism, can slow densification. Density is one of two major remedies for our housing affordability crisis — the other being removing tax concessions, which overstimulate demand.

Yet heritage defenders counter that overlays don’t prevent development; they merely ensure developments preserve certain unique architectural elements. The Australian Institute of Architects’ Robert Caulfield claimed the Carlton car park, for instance, could still be repurposed as housing, so long as the existing structure wasn’t demolished.

So, can we balance both heritage and development?

Heritage, commutes and affordability

In Sydney, analysis by Domain found there remains a high concentration of heritage listings in affluent inner-ring suburbs and virtually no listings in lower socio-economic areas. Experts found this “can prevent more housing being built in well-located, liveable suburbs”, which either pushes development further afield or lowers the overall housing stock.

In Melbourne, Domain found Albert Park was the city’s most expensive suburb per square metre. Why? As local real estate agent Warwick Gardiner explained, “The major drawcard is that it’s quiet … All the houses have a heritage overlay, so there aren’t masses of apartments.”

While developers can theoretically build on heritage sites, in practice the rules can be difficult to work around, leaving many worthy projects mothballed — and affluent areas free of pesky newcomers.

Planning minutia can be dominated by aloof urban history buffs, or war-gamed by established homeowners to indulge their change aversion and protect their property values. But when you’ve got younger and poorer people struggling to meet rising rent payments, spending hours commuting to and from work, and with dwindling prospects of homeownership, residents of one of Melbourne’s most expensive suburbs feeling a bit flustered by prospective changes are hardly the constituency our laws should be catering for.

Heritage listings should be reserved for buildings of true historic significance — particularly public buildings like historic pubs and cultural venues — lest our cities become private museums for dead architecture styles, which most living people can only visit after a two-hour drive.

Parking the anti-growth mindset

Heritage rules are just one of the many restrictions on housing supply that are making well-located properties scarce and expensive, all to the convenience of existing owners.

NSW Labor took a welcome cudgel to such rules last week by vowing to significantly increase density around metro stations and review councils’ housing targets if it wins the March state election. Its pledge is a modest start, but outdoes the Perrottet government, which reduced building heights and halved the number of new homes planned for the forthcoming Crows Nest Station on Sydney’s wealthy North Shore due to neighbourhood backlash.

Streets surrounding transport hubs are the best places to densify, allowing more people to live closer to public transport and reducing their dependency on cars. If we expedited such developments, perhaps we wouldn’t need so many car parks.

Are heritage listings worsening Australia’s housing crisis? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

100% agree with everything Benjamin states. Europe may lock down cities with heritage protection, but they already have the level of density that makes a city walkable/sustainable. Locking down 1 and 2 story private houses in the inner city forever is an act of sabotage against our children.

Here are two major remedies that might actually work:

* Force developers to use up their land banks building more new houses (more supply)

* Reducing immigration (less demand)

Or there’s the RBA’s solution:

* Make everyone poorer so they increasingly live in shared houses.

“Tax concessions” presumably mean negative gearing. Property investors primarily buy existing properties, not new ones and therefore don’t drive demand for new stock.

Agree with most of this. There will be many disgruntled nimbys if the NSW ALP follows through on that promise.

I work a bit in the heritage industry and have to admit that many heritage-listed properties shouldn’t be listed; they are often listed for being generic examples of different housing types or styles, rather than for excellence or significance, which is totally wrong-headed.

However its incredibly hard to make that argument in the inner suburbs; nimby = progressive is the assumption around here. Campaigns to save mediocre or insignificant buildings are routinely based on nostalgia and xenophobia. The SMH panders shamelessly to this audience.

Ah yes.

Anyone is favour of slowing population growth is a xenophobe and/or a NIMBY.

If you don’t have case go ad hominem.

I don’t want to live in a society composed increasingly of old people. Nothing against oldies, I’m one myself, but socially and economically that is the way to disaster. Every society needs a majority of younger, highly motivated people to for many reasons, including paying for the collective goods that society needs. If you live in some inner suburbs these days its like inhabiting a gated community. No thanks.

There’s a vastly expanding cohort of the very old now. You can’t keep shovelling in more young people to balance them out for ever. Those young people will live to 80 and 90 plus too.

What’s “old” ?

<40yos outnumber >40yos

Only just, barely correct for the moment – the median age is 38.4 and rising rapidly so in a year or two there will be MORE people over 40 than under.

The median age in non urban Australia is 41.8 – only the cities (37.1) skew the age pyramid.

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population-age-and-sex/latest-release

You clearly don’t work in the heritage space because you clearly don’t understand what the word “significance” actually means.

As for “Campaigns to save buildings that I can’t personally see the merit in are xenophobic” … why do people put their names next to such self-demonstrably stupid rhetoric?

I agree that applying statutory protection to a place in order to preserve it (effectively into perpetuity) for the public benefit should always be subject to community and expert scrutiny and debate.

But, this article- which I welcome, heritage is a dynamic that should be discussed more – reads like an opinion piece and should be classed as much by Crikey. It is far from a balanced take on heritage management in Victoria or elsewhere.

The assumption that urban heritage management and densification are mutually exclusive is an overworked cliche. Yes, the statutory authorities (councils + Heritage Victoria) should be more forthright in their acceptance of density in the historic environment as a valid aim, but it is absolutely achievable.

The heritage field in Australia has had a longstanding problem with speaking to the broader public about the benefits of the historic environment and the various ways in which it is managed, especially the publication of empirical studies. But a readily applicable discussion and analysis of this issue are contained in The National Trust for Historic Preservation (America) publication several years back of the ‘Older, Smaller, Better: New Research from the Preservation Green Lab’ report, which looked closely at the ‘hidden density’ achieved by streets that comprised a mix of old and new buildings, along with a myriad of other benefits brought about by the retention/adaption of the historic building stock. I encourage the author to at least glance at it or subject his viewpoint of heritage as anti-change to some probing from people working in this space.

Heritage listing is not incompatible with density aims, nor is it fair to lay gentrification or the ‘locking’ of affluent, older areas at the feet of built conservation. Heritage often becomes the fall guy for complicated urban, economic, and planning dynamics.

That identifying and managing significant historic environments establishes ‘architectural cemeteries’ is a new and catchy barb, but not one that equates with how places are determined to be of public value (a particularly rigorous process in Victoria) or how heritage is factored into decision-making about change. It is a remark that sounds crafted by the real estate, pro-development lobby rather than an article that purports to be delving into heritage.

Rather than join the Fairxfax press in their periodic assassination of the imperfect but hard-fought contemporary heritage system, Crikey should explore this issue in far more depth. Its deserves informed illumination.

There is a difference between a heritage listed building and a heritage overlay on an area. We need to preserve our Victorian era streetscapes, not turn our cities into dreary high rise canyons in the name of perpetual growth.

Why do we need to preserve our Victorian era streetscapes? As the article notes, Carlton and Sth Melbourne are full of single story Victorian cottages. 1km from the Melbourne GPO. Ridiculous. If you want to save the corner pubs and public buildings, go for it. They have a cultural value. I’d rather house my children than over-romanticise some iron lace on a verandah.

Paris only looks like Paris because they knocked down the poor first effort two hundred years ago.

Most European cities are very big on preserving their streetscapes. That’s why we like to visit them.

Because they are our heritage. They are what gives the city its entire civic identity. They are the ONLY thing unique about our built form and they are irreplaceable, and people fought very hard to preserve them. They are redevelopable at higher density, just not demolishable.