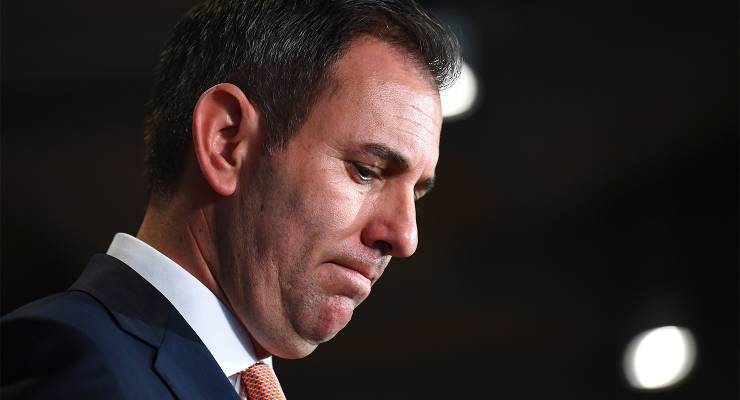

“People understand that we can’t do everything at once,” Treasurer Jim Chalmers said last month.

Similar “steady as she goes” talking points were parroted by Labor’s frontbench last week in response to increasing pressure to raise the rate of JobSeeker, including from the government’s own backbench and expert committee.

The message was we just haven’t reached the Right Time™ — when the government’s stars and chakras perfectly align to facilitate a politically and economically costless welfare expansion. Just hang tight and trust the process.

This framing not only ignores the fact recipients have been hanging tight for decades while politicians have subordinated their reasonable demands to countless frivolous boondoggles, or the issue’s moral and practical urgency — every day Canberra dithers is another day struggling recipients count their last coins and send their kids to school with empty lunchboxes.

It also assumes the policy terrain won’t get worse from here, that by the time Prime Minister Anthony Albanese arrives at substantive compassion on his sweatless stroll, the May 2023 budget won’t look like the Right Time™ in retrospect.

But there are enough storm clouds gathering, and enough present bright spots, to suggest the Right Time™ is now.

It’ll only get more expensive

Australia’s unemployment rate is nearly at a 50-year low. The number of JobSeeker recipients has accordingly declined, hitting its lowest level since the pandemic in March. This has heavily discounted the price tag for raising the dole.

The government should push to maintain full employment. But given the Reserve Bank is raising interest rates, and some of the inevitable consequences are rising business costs, higher redundancies and lower hiring, some job losses are likely. The International Monetary Fund predicts our unemployment rate to rise from 3.5% to 4% by December.

So sure, committing to a raise now will likely make the government liable for larger outlays in future. But that’s what shrewd governments do — capitalise on opportune moments to bake in their priorities, so even if costs grow over time, voter attachment and backflip aversion force alternative savings.

The budget will only get worse

Not only is the cost relatively cheap, but the government’s capacity to pay is temporarily secure. Thanks to booming commodity prices and low unemployment, Treasury’s tax receipts are much higher than expected. Economists believe Chalmers will even announce a small surplus at next month’s budget — indeed, the Finance Department confirmed a rolling surplus for the year to March.

The budget position is likely to deteriorate though, given the structural gulf between our meagre tax revenue and our ballooning commitments. Chalmers is probably destined to confront this shortfall eventually and, depending on his proposals, may not want to couple broad tax rises with handouts to the poor — for fear of handing populist slogans to Peter Dutton.

It’ll only get less popular

Which brings us to the question of electoral viability. As the AFR’s Phillip Coorey wrote on Thursday:

Senior Labor people confide there are no extra votes for the government in increasing welfare, but there are risks. Increasing the dole in a low unemployment environment, when every other shop or café on the high street has a ‘help wanted’ notice in the window, tends to foster resentment, especially among the low-paid such as cleaners, who work their guts out for not much more than welfare.

Aside from stretching the meaning of “not much more” — it’s 57% of the minimum wage — Coorey and his sources’ analysis is circular. We can’t raise welfare when unemployment is low because jobs are plentiful (despite the fact most recipients can’t work full-time due to sickness or disability). But we didn’t raise it pre-COVID when unemployment was higher due to cost concerns. In this conception, the Right Time™ is literally never.

Polling also shows relative support for a raise — 42% favour, 31% oppose, 26% unsure, according to Resolve. Other polls have put support at up to 55%. The electorate has been complicit with our heartless leaders in deprioritising this issue for decades, but we’ve reached a moment of relative public compassion.

But this support may weaken if the government later poses a link between welfare generosity and unpopular tax changes. Support is higher for other spending measures too, and as another election gets closer, pressure to prioritise sweeteners for swing voters and marginal seats will also rise.

It’s time

Albanese may have correctly calculated that bold progressive reforms are best not advocated for from opposition (though even this is debatable given the entangled variable of Bill Shorten’s popularity in Labor’s 2019 loss). But the prime minister’s concerted timidity has extended into government beyond reason, to the point of squandering opportunities. It’s as if he believes voters are not merely unreliably progressive but intractably conservative, always, on all but the most banal issues, even when many tell pollsters they aren’t.

Sure, there are powerful forces entrenching apathy and stubbornness, from financial self-interest to media hysteria. But surely to think Australia is irretrievably beyond lifting our most vulnerable citizens above the poverty line is a cynical misreading.

Hawke and Keating, those bold reformers so hallowed by Labor’s present leaders, raised unemployment benefits repeatedly (27% in total), including soon after Hawke’s first election when inflation was higher than it is now. Their actions substantially cut poverty.

Such legacies are not built on bided time and bitten tongues. The Right Time™ to raise the rate was the day Albanese took office. The second-best time is now.

Yep!

I’m writing thank-you to every Labor MP who I hear standing publicly in support of raising JobSeeker. I also tell them that I now also vote for a strong independent candidate because there are so few party MPs prepared to stand up for basic humanity and the national interest over party interests and their political ambitions (as they have in this case). Then I write to the PM and tell him that I’ve done it.

I’ve also written to the Labor senators in my state to explain they won’t be featuring amongst the top contenders when I mark my ballot papers in the future, and that Greens candidates will replace them.

I hope that through elections and polls and whining emails, they’ll eventually start to see that enormous numbers of us are becoming more and more disturbed by poverty and homelessness as they eat their way into parts of the community that used to be able to cover the basics and can no longer be hidden away.

Absolutely agree WW. I campaigned actively for a change of useless Govt, for which the lost 10 years really requires some form of retribution. And now, we are burdened with a spineless group of straw men, quite willing to sacrifice our most vulnerable on the altar of US militarism, sporting arenas, and the rest. Wake up Albanese. I am not alone in feeling this way. If we can afford numerous retired US military ” consultants” in Defence, some earning $7,000 PER DAY, then surely our disadvantaged deserve relief. Make it happen.

Patience! There are 9 years of damage to work through!

How many terms of government will we have to be patient before this centre-Right government finally develops a taste for boldness?

Until the heat death of the universe, at the earliest.

Good work. I too am beyond fed up with their foot-dragging and excuses, it beggars belief (see what I did there?). Seriously, it’s loathsome to see this inaction when people are sleeping rough or in their cars, this should never happen in a country as affluent as Orstrilia. I shall follow your example and do likewise with the emails and letters. Frickin’ disgraceful.

If Labor does not realistically raise Jobseeker and related allowances, and then goes ahead with the tax cuts to the wealthy, they’re dead not just to me, but to their base. This is the sort of egregious double standard is why people draw dicks and balls on their voting paper. What person not on two hundred thousand a year can maintain any faith in the system when the poor are so obviously screwed, and the rich are rewarded? This is how the MAGA forces got going. Democracy isn’t just dying, it’s being euthanized after a prolonged bashing.

I am on $200,000 per year, and I have trouble maintaining any faith in the system when the poor are so obviously screwed, and the rich are rewarded.

Everyone talks about the cost of $24B to do this, without mentioning that this is the cost over the next 4 years. So $6B per year, which will get spent and put back into the economy, just when economic activity seems to be faltering.

Yes, yes and yes!!! Sadly SSR may be right. What a horrible debacle we are witnessing!!! i really hope I’m wrong!!

The soi-disant democracy – as practiced throughout the anglophone West, some of the Continentals are hanging in – committed suicide once the Boomers got theirs as per their unentitled expectations.

Neil Postman’s “Amusing Ourselves to Death” (1985) laid out the danger well but, like too many seers, he was ignored when not derided.

Sorry to burst your assumptive bubble, Munin, but I’M a “Boomer” who didn’t ‘get mine’ – or even anything close to it.

There are plenty of so-called “Boomers” out here who are doing it just as though – and tougher since ageism is rife in the Australian employment environment – as any other impoverished citizen.

Stop putting us all into the same box because you find it convenient to blame us for this appalling mess and start realising that it is Neo-liberalism – gleefully embraced by the likes of Jeff Kennet, John Howard, Peter Costello and others – that has caused this rapidly-approaching-Dystopianism nightmare.

Any boomer who did not get their chunk was a wastrel or not trying.

Peeps be weird then whine about the consequences.

Tax Cut Stage 3 applies to salary starting at 45k. Don’t think people on 45k are rich ….. Just saying …..

People between 45k and 120k will pay more in taxes from this year onwards.

yep when cancelling the tax 3 cuts people between 45k-120k are getting penalized twice. First paying more taxing this year and not getting the tax stage 3 cut

Complete cancellation not necessary. Plenty of room to adjust the scale of the tax cuts, and the proposed tax scales as well, so the truly well-off don’t get a cut and the progressivity of the tax system is retained.

Since stage 3 tax cuts are already legislated that would require changing existing law which is difficult. Easier to cancel it ….

Laws are being changed all the time. And to change this particular one wouldn’t be difficult as the Coalition would be pretty much alone in opposing it.

It has nothing to do with timidity and the article is missing the government’s rationale by arguing based on economics and budgets. Albanese set out to get elected by promising to govern like a Liberal and to keep Liberal policies. He knows this worked because he is PM. He now intends to prove he will not flinch from following through on being a Liberal to the bitter end. He expects this to keep Labor in power indefinitely, because Labor is offering Liberal voters a far superior Liberal party than the Liberals can manage. Any Liberal voter with any sense can see Labor is the better Liberal party. Labor does not worry about Labor voters or those on welfare because they are not going to vote Liberal whatever Labor does. The plan is working, the Liberal Party is crumbling away, and Albanese is not going to let up.

That is so horribly true.

Good analysis. Sadly, from what I’ve seen so far, spot on SSR.

Nailed it SSR. Pity, but it still irks me mightily that 6bn a year if held back for the unemployed, while multi billions are wasted on tax cuts for the wealthy and the American military machine. I predict there won’t be many traditional Labor votes around next election – they will go to Green or Independent. Then see what happens to Albo’s Liberal supporters . . .

Absolutely spot on!! Of course not everything can be done at once!! So how about starting with the most important things first?? Like a modest windfall tax on the excessive profits being made by gas and oil producers. Then a revamping of the tax cuts; smaller and fairer (again, modest tax relief for those who need it most, including raising the tax-free threshold). And finally, increasing the Jobseeker rate as recommended by the Govt’s own sub-committee.

As an ALP member, I’m both disappointed and becoming angry. Albo & Chalmers could be Labor heroes, however at this stage they are heading towards becoming ‘rats’, like that despicable Anna Bligh!! If there is no sign of a ‘Labor Government’ very soon, I will be supporting David Pocock as ‘my’ Senator from the ACT

The Silver Bodgie was the best PM the Liberals could ever have dreamed of having – he & his ilk did all the union busting, condition slashing and tenure abolition that existed in their wet dreams but lacked the courage or support to ram through.

Perfectly said. I remain stupefied by how many ostensibly progressive members of ‘the comfortable class’ on Twitter stubbornly remain inured to this outrageously unconscionable neoliberal reality. Albanese’s shameless schtick is now so particularly offensive, I literally can’t tolerate listening to this ‘Labor’ party PM (head quisling) for the remainder of his accursed term – which may well be interminably, unless sufficient numbers of equally alarmed and stupefied Australians finally damn well react with well overdue revulsion.

Surely people have had it with this Emperor’s New Clothes utterly transparent neoliberal bullshit, and the nearly irreversible damage already upending that collective memory of the social good aka ‘society’.

(Or is self-interest genuinely past the point of no return – ‘Labor’s’ cynical confirmation and calculation of there being no votes in involving/invoking precepts of decency or humanity).

And also (maybe) genuinely blind drunk on the neoliberal kool-aid he’s been imbibing for years – but definitely not explained by simple ‘timidity’.

They had a great communicator once in Peter Garret and they garroted him quick smart. He was okaying stuff he once would never have okayed in no time at all. Richard Marles must belong in a dominating faction, because he’s the most wishy-washy say-nothing excuse for vested interests we’ve got. I turn off when he’s interviewed because of the acute embarrassment I feel – not for him, for us.

Ditto re Marles, I squirm when he’s interviewed, opting to either leave the room or the TV channel.

Double ditto. But the big media like him, and don’t treat him like a twat because he’s ‘Defence’ and spending up big on anti-China implements.

How true All the econocrat commentariat are out there pushing the view that it’s unaffordable and inflationary The line that an increase will dampen incentive to work is also there This one has been around since Britain’s report into the poor law back in 1834

All the economists Ive read are in favour of the increase because it won’t be inflationary (it will just let people catch up on the bills and keep them under control), won’t dampen incentive (because unemployment is now so low, most people unemployed for a period of time are unwell or have a disability and can’t work) and people who are suitable for work are struggling to apply for work (because they can’t afford to go to interviews, get new qualifications, etc).

This is the choice of the Treasurer and the PM because they think it’s a vote winner.

That’s it, in one sentence, your last. Albo has his ear tuned to the lowest common denominator ‘out there’ in the places where those with ‘downward envy’ live.