It’s more than eight years since the heady days that followed my release from Egypt on terrorism charges back in 2015.

At the time, I was hugely relieved to be at home, in a country that seemed committed to media freedom. You’ll appreciate that after Egypt, that mattered a lot to me. As the dust settled, I began to think about the deeper reasons I’d wound up in Cairo’s notorious Tora Prison.

Back then, the Egyptian government had taken the national security rhetoric that swept across the world in the wake of 9/11 and given itself wide powers that it then used to lock up anyone who challenged the official narrative. Including me. In broad terms, it had used loosely framed national security legislation to come after uncomfortable journalism.

The more I looked at our own country, the more I realised that we too had the same political winds, driving us in much the same direction. I am not being dramatic here. Since 9/11, successive Australian governments of all stripes have passed almost 100 separate pieces of national security legislation — more than any other country on earth. One Canadian researcher called it “hyper-legislation”, and that was back in 2010 when we’d only had 50 new laws.

In early 2019, my organisation, the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom (AJF), published a white paper on press freedom and national security in Australia. In that document, we argued that because Australia does not have any explicit constitutional or legislative protection for media freedom, many of the laws had either directly or indirectly intruded on the media’s ability to perform its democratic role in holding governments to account.

Our white paper said the laws had criminalised much of what previously would have been considered legitimate reporting of government affairs. We said journalists’ data had been exposed to intrusive police investigation, and crucially for this event, that journalists’ sources — whistleblowers — were dangerously exposed and liable to prosecution.

We published our white paper two weeks before the Australian Federal Police first knocked on the door of News Corp’s political correspondent Annika Smethurst in search of evidence of the sources of one of her stories. The next day, they went to the ABC’s Sydney headquarters to do the same thing.

In other words, we saw — guess what — a government using loosely framed national security legislation to come after uncomfortable journalism.

After the raids, The New York Times did a deeper dive and declared: “Australia may well be the world’s most secretive democracy”.

The Times listed several reasons for its bold statement, starting with the lack of any explicit constitutional protection for media freedom. It then pointed to our draconian secrecy laws, which provide heavy jail terms for whistleblowers who expose official information — even when it is in the public interest.

Last month, I wrote an opinion piece for The Sydney Morning Herald arguing the laws protecting whistleblowing and media freedom were manifestly failing, and contributing to a deeply troubling culture of secrecy that has found its way into every level of government here.

I got a rather upset response from the Attorney-General’s Office, complaining that I’d failed to acknowledge the work they’d done to fix these problems.

I might have been a bit harsh in that piece. The government has passed National Anti-Corruption Commission legislation that includes some protections for journalists and their sources. It has passed amendments to whistleblowing laws, and Mark Dreyfus has commissioned a review of Commonwealth secrecy offences to see if the laws adequately protect public interest journalism. He’s also dropped the charges against Bernard Collaery and the government has said it will implement the recommendations of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security that it made in the wake of the AFP raids. There is also work to harmonise state shield laws that protect journalists in court.

All that is laudable. But they are patches stitched on to legislation that hides a deeper problem. And it goes back to that lack of any explicit protection for media freedom.

The ideal would be an amendment that writes the principle into the core of our constitution, just like every other liberal democracy. But given the experience of last weekend’s referendum, I reckon our chances of getting constitutional protections for journalists are about as high as getting cane toads protected.

But the AJF has a solution. We are proposing a Media Freedom Act that would work in ways very similar to the Human Rights Acts in Queensland, the ACT and Victoria. There, the laws do three simple things: they compel Parliament to always consider human rights whenever they’re passing new legislation, they ensure courts must always interpret existing legislation in ways that privilege human rights, and they make civil servants act in ways that support human rights. If we simply replaced the words “human rights” with “media freedom”, I think we would be close to a solution that could have profound implications for the relationship between the government and the media, and through them, for the people both are supposed to serve.

In effect, we would inject a positive obligation to consider the importance of press freedom at every stage of the process. I am not arguing that it must always trump everything else all the time. But because it is such a key part of any democracy, we must have a mechanism that takes the role of journalists and whistleblowers into account.

Let’s go back to those 2019 raids to see how our Media Freedom Act might work.

Remember — in neither case did the journalists publish anything that genuinely damaged national security. The police were investigating their sources simply because it is an offence to disclose classified documents. It didn’t matter what was in those documents or why they were disclosed.

To be clear, I have some sympathy for the police. They were just doing their jobs. They had evidence that laws were broken, and they had a legal obligation to investigate. But the journalists were also doing their jobs. It was indisputable that the stories they exposed were genuinely in the public interest, and they too had an ethical obligation to protect the whistleblowers who gave them the documents in the first place.

Given the way the story of the raids exploded here and abroad, I suspect everyone involved would have preferred to avoid that rather ugly mess.

Our Media Freedom Act gives us a way out. It requires the police and the judge issuing a warrant to balance the public interest in protecting press freedom against the public interest in continuing the prosecution. If there is a compelling case for why the investigation trumps publication… no problem. But it would be hard to do that for stories that clearly expose wrongdoing, and where there is little demonstrable cost to national security.

Our act would inject a presumption in favour of publishing, and of the protection of sources, into the core of our legal code.

In a lot of the conversations that followed the raids, we were asked about how to strike the balance between press freedom and national security. That is the wrong way to think about it. It implies a false binary. The idea of “balance” suggests that if you have more of one, you necessarily have less of the other. But what we have seen in recent years is that whistleblowers working with responsible journalists actually enhance national security. They expose the failures of our security agencies, they provoke important public debates about our national priorities, and they maintain that transparency so important to an effective democracy.

In short, we should consider both media freedom and whistleblowing as integral to our national security system — not in opposition to it.

This is why I am here as a media freedom activist. Whistle-blower protection is a media freedom issue. It’s what I sometimes describe as the “chain of disclosure”. Any broken link in that chain damages the integrity of the system of transparency.

I know the government broadly agrees. That’s why we’ve seen the reforms I mentioned earlier. But while those are welcome steps, patching legislation here and there simply isn’t enough.

Mark Dreyfus was on the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security as the shadow attorney-general when it published that report about press freedom after the 2019 raids. At the time he wrote a dissenting opinion in which he said the recommendations were the bare minimum for reform — the starting point, not the end of it. We agree. That’s why we think a Media Freedom Act is the way forward.

We also know it’s a big reform. It’s going to take time and effort. So here are some other things the government should be doing now.

A coalition of groups including the Human Rights Law Centre, Griffith University and Transparency International Australia has published a clear and straightforward roadmap for whistleblower protections.

The group acknowledges the legislative changes the government has already made, but it says they are minor and technical. It argues that without more substantial reforms, they’re unlikely to make a material difference to the experience of whistleblowers. The government has promised more action, but we still haven’t seen the details.

We also need an independent whistleblower protection authority to oversee and enforce the laws and support whistleblowers. That’s not revolutionary — there are many similar bodies in the US, Slovakia, the Netherlands and elsewhere.

But the most straightforward thing also seems to be the toughest. The attorney-general needs to drop the prosecutions of the two most prominent whistleblowers in Australia today.

There’s Richard Boyle — the tax office official who exposed its corrupt and unethical debt collection practices in South Australia. He tried to complain internally, but the complaints were dismissed, so he went to the ABC. The story triggered national outrage and changes to the ATO’s practices. And Richard’s reward? A ruined career, mental health challenges, and dozens of charges related to illegally recording phone conversations and protected information. His trial is due to start next year.

The other case is David McBride — a military lawyer for the special forces. He found evidence that some Australian SAS troops had murdered unarmed civilians in Afghanistan. David compiled a dossier that he took to his superiors and later to the Australian Federal Police. When nothing happened, in line with his understanding of whistleblowing law, he went to the ABC. They turned it into what became known as the Afghan Files.

And in less than a month, we will see the first trial in relation to those documents. But it won’t be any of the soldiers accused of committing the crimes. It will be David, the whistleblower. He has pleaded not guilty to five charges including the unauthorised disclosure of information, theft of Commonwealth property and breaching the Defence Act.

David’s case is, I think, a good example of the way in which laws designed to protect national security can sometimes undermine it.

Years after the Afghan Files story broke, the Brereton report into alleged war crimes vindicated the leak and the ABC’s journalism. It has forced the military to rethink its culture. And it’s likely we will see prosecutions of some of the SAS soldiers accused of breaking the laws of war. The whistleblowers and the journalists helped, not hindered, Australia’s national security.

Given all that, it is hard to see how the prosecutions of McBride and Boyle can possibly be in the national interest. Their cases matter. Obviously, there is the narrow moral question of whether it is right that they be punished for what they exposed, but they also matter for the signals that they send across Australia. How can anyone take the attorney-general’s commitment to protecting whistleblowing at his word, when the two most prominent examples are heading to court, and quite possibly prison?

Back in 2020, the then-opposition leader Anthony Albanese spoke to Crikey about the case of Bernard Collaery who was also facing prosecution at the time.

Mr Albanese said, and I quote, “The idea that there should be a prosecution of a whistle-blower, for what’s a shameful part of Australia’s history, is simply wrong”.

It’s hard to see how his remarks back then wouldn’t apply to both Richard Boyle and David McBride now.

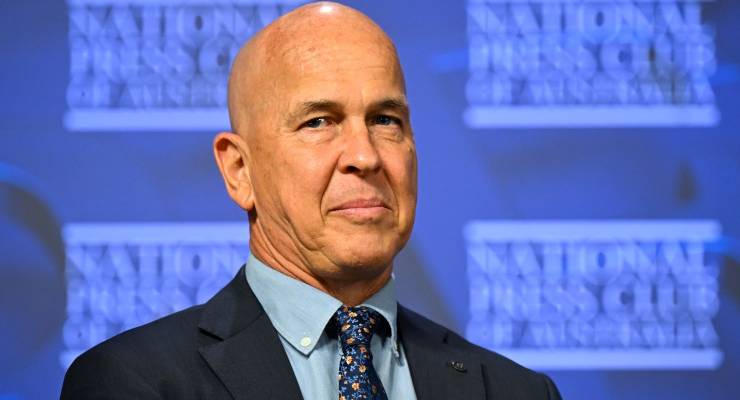

This is an edited extract of a speech delivered by Peter Greste to the National Press Club on 17 October 2023.

Why still publishing this Quisling and Establishment toadie?

I scanned his bloodless bucket of bilge looking for a certain name

In vain, as expected.

No mention at all of a bloke who shames all the line toeing, overpaid under delivering, prima donnas masquerading as journalists for their total lack of integrity, courage, principle and guts.

If anything, by constantly avoiding any mention of this martyr’s name he shows that he is fully aware that doing so will recall his own pusillanimity in return for big buck$

Just a hint – starts with A and ends with SSANGE.

Hm, although rather understated and perhaps overly polite, those last four paragraphs are reasonably damning.

Interested in this Assange angle; what was the payoff for old mate? A quick squiz at some stuff he’s said elsewhere about Assange reveals a nuanced position, accepting both good and bad aspects of the guy.

Greste is part of the establishment these days – part of the contract I guess?

He does not, in any way, consider Assange to be a journalist. In April 2019 he stated:

’To be clear, Julian Assange is not a journalist and Wikileaks is not a news organisation. There is an argument to be had about the libertarian ideal of radical transparency that underpins its ethos, but that is a separate issue altogether from press freedom.

Journalism demands more than simply acquiring confidential information and releasing if unfiltered onto the internet for punters to sort through.’

For sure, much better the have ‘unfiltered’ information ‘curated’ by those who know better – you know, the US State Department. Greste is an empty suit.

Less than an empty suit which would at least be useful to give to someone needy.

He was only ever a churnalist who rewrote press releases from Langley VA which is why he was banged up in Egypt – Morsi was still in power after the orchestrated F/B Spring and not following orders.

El-Sissi had not yet assumed his rightful place as the USA satrap following his 2006 term enrolled in the United States Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Whistleblower protection is an urgent issue in the health industry worldwide, to take a single but hugely important facet of the war on truth. Unintentionally or otherwise, the argument that we have to win the war on Assange before we can make progress on anything else is so unhelpful and destructive. You wonder where it comes from.

Greste does not mention Assange because Greste wants the position of Great Australian Martyr Journalist all to himself alone. He really hates Assange taking any of that from him. He’s just a jealous guy…

No Australian government will agree to further relaxation of whistleblower laws lest they be embarrassed by the revelations.It would happen only via a minority Labor govt overwhelmed by Greens & independents. Greste is naive to think otherwise.

And no mention of Australia’s most discussed whistleblower, Julian Assange. Surprise surprise…

Free Julian Assange

“Assange”?