They worked room to room in the workers’ quarters in the hot Palestine night air, pulling out men and shooting them point blank, execution-style. A hundred deaths in all, a precise number sent by the commander, who had coolly decided on the atrocity as necessary to instil a local terror.

The event, as the reader may have guessed from me raising it, was not a Palestinian atrocity but a Zionist one, 75 years ago, in the villages of Hawassa and Balad al-Shaykh (detailed in Benny Morris’s account of the war, 1948), one of the first committed by the Haganah, the main force of the Zionist uprising.

Indeed, the Balad al-Shaykh massacre marked a turning point in the 1948 war to create Israel — a beginning of the use by mainstream Zionist forces of mass civilian terror as part of a strategy to win the war. What would follow was a war that drew civilian terror into the heart of such struggles, in the region and the world. Why raise it now, a long lifetime later? In the midst of a construction of what constitutes barbarism, what constitutes restraint and who wields which, it seems worth considering the complex history of terror and its uses.

In 1948 the Arab-Israeli War had begun in Palestine after the British had abruptly quit the place. They had been running it as a “mandate” since the end of World War I, after the break-up of the Ottoman Empire. By the time World War II started, hundreds of thousands of European Jews had entered the area, stirring up violent Arab resistance. Arab violence had prompted revisionist Zionists — those who believed Israel would have to be established by force — to form the IZL, or Irgun, which began terrorist attacks against Arab and British civilians.

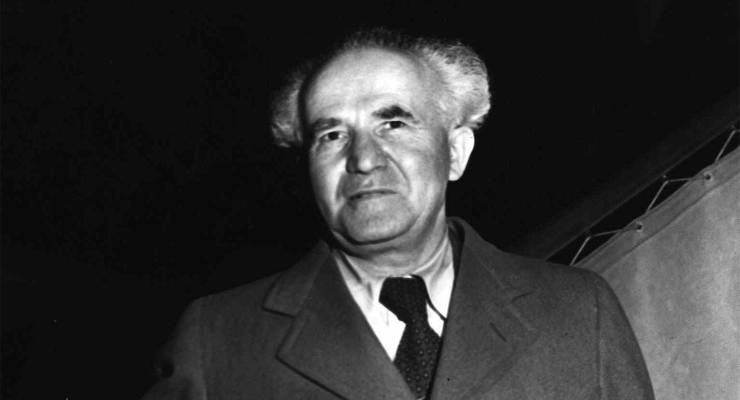

The Irgun’s strategy had been rejected by the mainstream Zionist elite force, the Palmach. But in the scramble of the guerrilla war to create Israel, the Palmach began to take up Irgun tactics. In the immediate aftermath, Morris notes, Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion defended the massacre as necessary, following tit-for-tat massacres first by an Irgun force on Arab workers at a bus stop, followed by reprisals by Arab workers. From then on, civilian-directed terror became a mainstay of the Zionist military operation, applied far more systematically than by Arab forces.

The Irgun had peeled off from the political Zionist movements in the 1930s to deal out precise and focused terror attacks against Arab and British civilians and British troops. Its model was the IRA, as reorganised by director of intelligence Michael Collins in World War I. Collins switched the application of violence from British officers and troops to softer targets, such as British sympathisers and petty informers, sending out squads of bicycling irregulars to slit throats with cut-throat razors. The British soft power network collapsed, and everyone in the empire learnt a lesson. Terror, hitherto directed at tsars and presidents, the most guilty, was most effective against empires when directed at the relatively innocent — essentially privatisation of the state terror by which empires were created.

Amid ample violence by Arabs against Jews, the Irgun’s innovation was the combination of utter randomness — civilians as targets — and utter precision. Largely forgotten today, it was a scandal of the time, with the notion of “Jewish terrorists” suggesting a certain type of depredation, held to be distinctly Jewish in character (confusingly, the terrorists themselves argued a version of this, with the leader of Zionist militant group Lehi and future Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir contending that Mosaic moral law permitted, indeed demanded, terrorist strategies).

The Irgun suspended operations against the British when World War II began. A split-off, the Lehi (known by the British as the “Stern gang”), did not. Small and extreme but nevertheless influential, the Lehi several times sought weapons from Nazi Germany to fight the British, arguing that Zionism, like Nazism, was a naturally totalitarian movement.

When World War II concluded, Irgun atrocities resumed, against both Arabs and British, with barrel bombs in markets, assassinations of British government officials, and a signal event of modern terror: Irgun leader and future Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin’s 1946 destruction with explosives of the King David Hotel, which had both military and civilian wings. The bombs placed in the latter killed 90 British, Arabs, Jews, Greeks and Armenians.

Though the world had just lived through an apocalyptic war, such operations — coming out of the blue — introduced something new to the world. Begin had learnt from Collins and the IRA that terror worked against rulers of weak resolve. The British had no desire to run Palestine, and it was an even more focused terror event that finally had them quit. With three convicted Irgun terrorists due for execution in July 1948, the Irgun abducted two British sergeants and, when the terrorists were executed, hung the sergeants and booby-trapped their bodies with explosives.

The event created near-hysteria in Britain, sparking a wave of anti-Semitic attacks. The macabre theatre of it — the sergeants’ weeks of contemplated death, followed by bodily desecration — prompted a wave of revulsion. Numerous pro-Zionist gentiles broke with the movement. But it had exactly the effect the Irgun had hoped, creating a sharp division between themselves and their cause, and everyone else, a glittering ruthlessness. It was disgust mobilised as a weapon, and it directly prompted the British withdrawal.

The Palmach did not long hold the Irgun and Lehi at arm’s length once the war for Israel began. It rapidly became clear that “cleansing” an area from Jerusalem across to Tel Aviv-Jaffa on the coast, and down to Gaza, was necessary if a country was to be created.

This necessitated “Plan D”, the systemic destruction of hundreds of Arab villages, and the expulsion of their residents, many of whom had lent no support to the Arab attack on the Zionist forces. Commanders of the Haganah (the Palmach’s military wing) and Irgun were given free rein to achieve this as they saw fit.

The most notorious of the civilian massacres that resulted was Deir Yassin, a village near Jerusalem, where more than 100 adults and children were slaughtered by Irgun forces. Once again, this terror was effective, the story of it setting thousands of Arabs fleeing east and south. For years, Deir Yassin was held up as a singular example of atrocity. But as the later work of historian Benny Morris and others showed, working from Palmach archives, it was one of dozens of such attacks, with varying body counts. Simple terror had become applied atrocity. In a 2004 interview in Haaretz publicising his revised edition on the period, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Morris noted:

What the new material shows is that there were far more acts of massacre than I had previously thought. To my surprise there were also many cases of rape … in a large proportion of the cases, the event ended with murder … They are just the tip of the iceberg … that can’t be chance. It’s a pattern…

Sa’Di and Abu-Lughod (eds) Nakba Columbia UP, chapter one

With cleared territory thus established, Israel could come into being. As the war wound on, some of the violence became in part the Irgun asserting itself against the larger Palmach organisation. Deir Yassin had been a strategic use of sadism and deep terror. Before the full massacre, the civilian men captured were taken into Motza, a Jerusalem neighbourhood, paraded, beaten and tortured in public, before being returned to the village and killed with the women and children in a quarry, after which the bodies were looted (Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, pp238-240).

Now, the Irgun attacked the city of Jaffa as a way of securing its own victory (despite attempts of both Jewish and Arab citizens to broker a peace deal), killing hundreds of Arabs, many fighting back, and according to Palmach reports, engaging in large-scale mutilation (Morris, 1948, p149; 1948 is also the source for the opening paragraphs). The volumes cited cover numerous other atrocities of these types.

How did this pattern of ruthless terror get so edited out of history? How did it come to seem that Zionism fought clean? Like Australian history, the true history is not taught — either inside or outside Israel. Many who hear of it simply pretend not to have. And there was no shortage of Arab violence against civilians at the time, detailed throughout the sources. That is not in dispute. But the forgetting of the crucial role of Zionist terrorism has given the use of atrocity a racist construction in the present.

It was also obscured, however, because the Palestinians adapted and updated the practice of terror after the 1967 war. Seeing themselves as invisible in the eyes of the world, the Palestinians combined terror with ’60s-era popular culture and performance-art “happenings” to create events both symbolic and lethal — planes exploding on runways, massacres at the Olympics, overseas assassinations of Israeli and Zionist officials.

These acts were more spectacular, and added an element of the visible grotesque to terrorist tactics, but they were not significantly more ruthless or violent than what had gone before. Yet it occluded the memory of no-less lethal or ruthless Zionist terror, and thus it remains. Just as the Irgun knew their acts would draw the attention of the world as well as its revulsion, so too the Palestinians in the ’70s and ’80s knew that they would be labelled as “animals” and notions of barbarism deployed against them — the price of making the world see and react. So too with the most recent Hamas raid, a new Deir Yassin on a larger scale. That this is coolly intended is shown by the Hamas terrorists’ use of bodycams — which have provided the footage Israel is showing to the global press corps.

Such terror is indefensible, but it seeks the very opposite of solidarity. It is reached for when appeals to solidarity have failed. Instead, it attempts to fundamentally reshape the world, cleaving past from present. In creating a situation in which Israel’s actions are dictates against prudence by the rage of its population (and the very mysterious behaviour of its military-political elite), Hamas’ terror has surely succeeded for the moment against an enemy whose application of the practice largely created the larger situation seven decades earlier.

Such terror, far from being barbaric or medieval, is impeccably modern, the manipulation of affect for clearly conceived aims. Seventy-five years ago — history, the blink of an eye, someone’s lifetime that never got lived — is worth remembering in the slaughter that is to come.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.