With a few keystrokes and clicks, anyone can make Skye do whatever they want.

You can put the 22-year-old Australian woman on a fashion runway, against a streetscape or in a garden. She will wear a T-shirt or a skin-tight dress. Skye might smile cheekily over her shoulder or stare blankly. She will do literally anything you tell her to — thanks to artificial intelligence (AI).

Skye, a pseudonym granted to protect her identity, is a real person. But she’s also become the source material for an AI model. Someone has trained an algorithm on photographs of her so that it can create completely new images of her. Anyone can use it to create a photorealistic image of her that will follow their specifications about everything including choice of outfit, image style, background, mood and pose. And the real Skye had no idea someone had done this to her.

Thriving online communities and businesses have emerged that allow people to create and share all kinds of custom AI models. Except once you scratch below the surface, it is evident that the primary purpose of these communities is to create non-consensual sexual images of women, ranging from celebrities to members of the public. In some cases, people are even making money taking requests to create these models of people for use.

Skye is one of the Australians who’ve unknowingly become training material for generative AI without their consent. There is very little recourse for victims as the law in some jurisdictions has not kept up with this technology, and even where it has it can be difficult to enforce.

Over the past few years, there have been huge advances in generative AI, the algorithms trained on data to produce new pieces of content. Chatbots like ChatGPT and text-to-image generators like DALL-E are the two best-known examples of AI products that turn a user’s questions and prompts into text responses or images.

These commercial products offered by OpenAI and their competitors also have open-source counterparts that any person can download, tweak and use. One popular example is Stable Diffusion, a publicly released model already trained on a large data set. Since its release in 2022, both people and companies have used this as the basis to create a variety of AI products.

One such company is CivitAI which has created a website of the same name that allows people to upload and share AI models and their outputs: “Civitai is a dynamic platform designed to boost the creation and exploration of AI-generated media,” the company’s website says.

It first drew attention after 404 Media investigations into how the company, which is backed by one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent VC funds, is making money off hosting and facilitating the production of non-consensual sexual images; has created features that allow people to offer “bounties” to create models of other people including private individuals; and had generated content that one of its co-founders said “could be categorised as child pornography”.

One of CivitAI’s functions is to allow people to share and download models and the image content created by its users. The platform also includes information about what model (or multiple models as they can be combined when creating an image) was used and what prompts were used to produce the image. Another feature offered by CivitAI is running these models on the cloud so that a user can produce images from uploaded models without even downloading them.

A visit to their website’s homepage shows AI-generated images that have been spotlighted by the company: a strawberry made out of jewels, a gothic-themed image of a castle and a princess character in the style of a fantasy illustration.

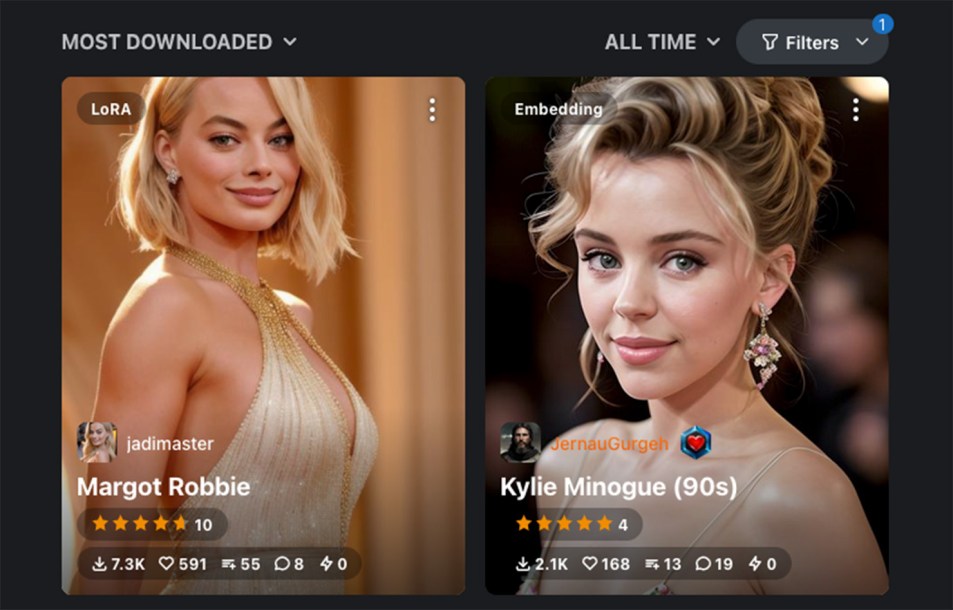

Another click shows many of the most popular models shown to logged-out users are for creating realistic images of women. The platform’s most popular tag is “woman” followed by “clothing”. CivitAI hosts more than 60 models that have been tagged “Australian”. All but a handful of these are dedicated to real individual women. Among the most popular are public figures like Margot Robbie and Kylie Minogue (trained on images from the nineties so it captures her in her twenties) but it also includes private individuals with tiny social media followings — like Skye.

Despite not being a public figure and having just 2,000 followers on Instagram, a CivitAI user uploaded a model of Skye with her full name, links to her social media, her year of birth and where she works late last year. The creator said that the model was trained on just 30 images of Skye.

The model’s maker shared a dozen images produced by the AI of Skye: a headshot, one of her sitting on a chair in Renaissance France and another of her hiking. All are clothed and non-explicit. It’s available for download or use on CivitAI’s servers and, according to the platform, has been downloaded 399 times since it was uploaded on December 2.

The model was trained and distributed completely unbeknownst to her. When first approached by Crikey, Skye hadn’t heard about it and was confused — “I don’t really understand. Is this bad” she asked via an Instagram direct message — but soon became upset and angry once she learned what had happened.

It’s not clear what kind of images the model has been used to create. Once users download it, there’s no way to know what kind of images they produce or if they share the model further.

What is clear is how most of CivitAI’s users are using models on the website. Despite its claim to be about all kinds of generative AI art, CivitAI users seem to predominantly use it for one task: creating explicit, adults-only images of women.

When a user creates a CivitAI account, logs in and turns off settings hiding not safe for work (NSFW) content, it becomes obvious that the majority of the popular content — and perhaps the majority of all of the content — is explicit, pornographic AI-created content. For example, nine out of 10 images most saved by users when I look at the website were of women (the tenth was a sculpture of a woman). Of those, eight of them were naked or engaging in a sexual act.

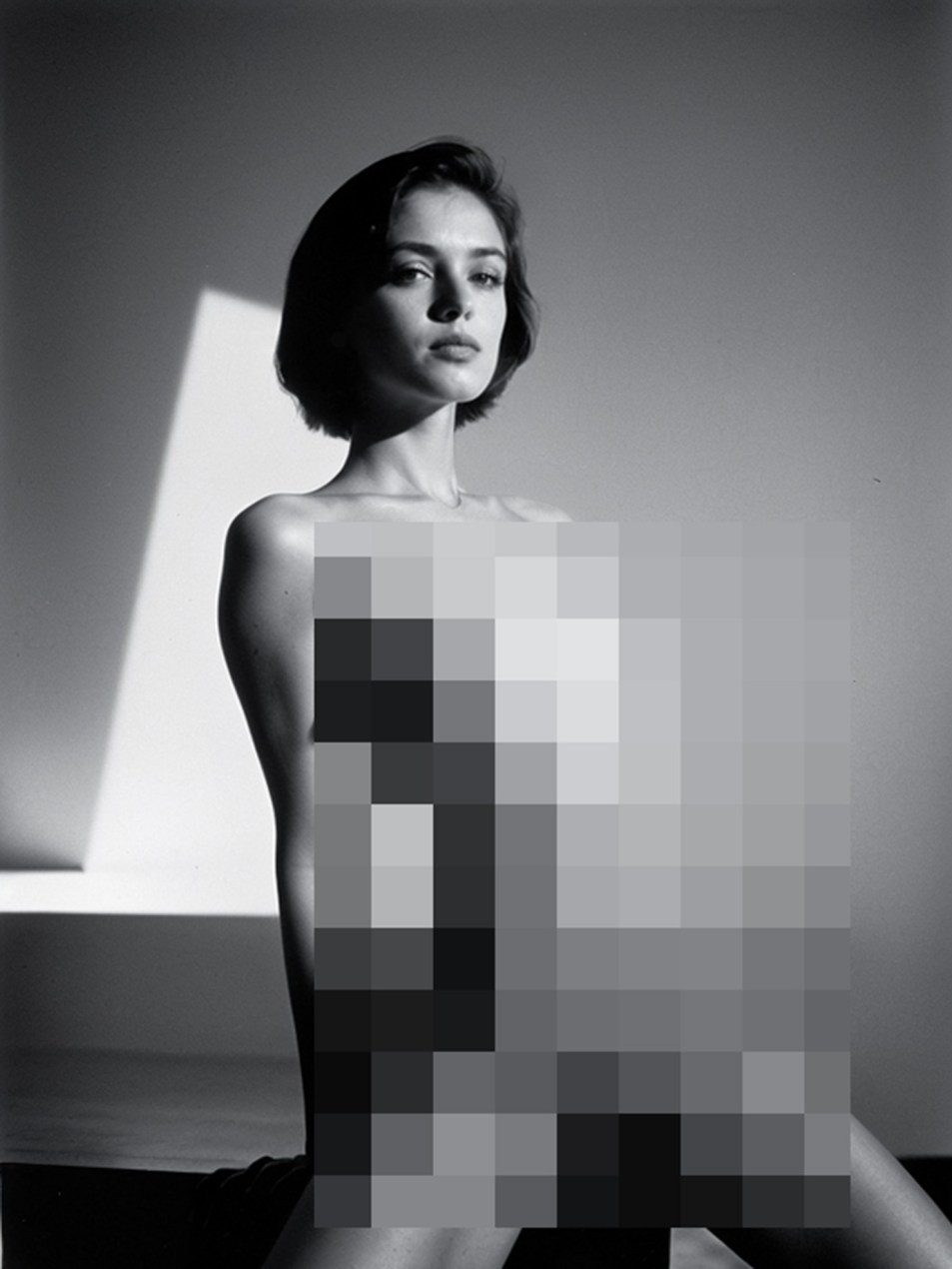

For example, the most saved image on the website when I looked was what looks like a black-and-white photograph of a naked woman perching on a bench that was uploaded by fp16_guy a week ago.

It specifies that it used a model called “PicX_real”, also created by fp16_guy, and the following prompts:

(a cute girl, 22 years old, small tits, skinny:1.1), nsfw, (best quality, high quality, photograph, hyperrealism, masterpiece, 8k:1.3), mestizo, burly, white shaggy hair, legskin, dark skin, smile, (low-key lighting, dramatic shadows and subtle highlights:1.1), adding mystery and sensuality, trending on trending on artsy, concept art, (shot by helmut newton:1.1), rule of thirds, black and white, modern.

These models also use what’s known as negative prompts — think of these as instructions for what the AI should not generate when creating the image. The image from fp16_guy has the following negative prompts:

mature, fat, [(CyberRealistic_Negative-neg, FastNegativeV2:0.8)::0.8]|[(deformed, distorted, disfigured:1.25), poorly drawn, bad anatomy, wrong anatomy, extra limb, missing limb, floating limbs, (mutated hands and fingers:1.3), disconnected limbs, mutation, mutated, disgusting, blurry, amputation::0.6], (UnrealisticDream:0.6)}

The end result is an explicit image that appears to be a convincing photograph of a woman who does not exist. The prompt calls for a generic “cute girl” which is created as what is essentially a composite person based on images analysed to create the AI model. If you weren’t told otherwise, you would assume this is a real person captured by a photographer.

Using technology to create explicit images or pornography isn’t inherently problematic. The porn industry has always been at the cutting edge of technology with the early adoption of things like camcorders, home VCRs and the mobile internet. AI is no exception. Adult content creators are already experimenting with AI, like a chatbot released by pornstar Riley Reid that will speak with users through text and generated voice memos. In fact, producing explicit images with AI is not fundamentally different to existing methods of “generating” images like sketching. Other industries have found legitimate uses for this technology too; a Spanish marketing agency claims to be making thousands of dollars a month from its AI-generated influencer and model.

But the reality is that the most popular use of this website and others like it is to generate new images of real people without their consent. Like Photoshop before and then AI-produced deepfakes — the videos that have been digitally altered to place someone’s face on someone else’s body — technology is already being used to create explicit images of people, predominantly women, in acts of image-based abuse. It might not be fundamentally different but generative AI models make this significantly easier, quicker and more powerful by making it possible for anyone with access to a computer to create entirely new and convincing images of people.

There are examples of Australians whose images have been used to train models that have been used to create explicit images on CivitAI’s platform. Antonia, also a pseudonym, is another young woman who’s not a public figure and has fewer than 7,000 Instagram followers. Another CivitAI user created and uploaded a model of her which has been used to create and post explicit images of her that are currently hosted on the platform. The user who created the model said it was a request by another user and, on another platform, offers to create custom models for people for a fee.

CivitAI has taken some steps to try and combat image-based abuse on its platform. The company has a policy that does not allow people to produce explicit images of real people without their consent, although it does allow explicit content of non-real people (like the composite “cute girl” image from before). It also will remove any model or image based on a real person at their request. “We take the likeness rights of individuals very seriously,” a spokesperson told Crikey.

These policies don’t appear to have stopped its users. A cursory glance by Crikey at popular images showed explicit images of public figures being hosted on the platform. When asked about how these policies are proactively enforced, the spokesperson pointed Crikey to its real people policy again.

Even if these rules were actively enforced, the nature of the technology means that CivitAI is still facilitating the production of explicit images of real people. A crucial part of this form of generative AI is that multiple models can be easily combined. So while CivitAI prohibits models that produce explicit images of real people, it makes it easy to access both models of real people and models that produce explicit images — which, when combined, create explicit images of real people. It’s akin to a store refusing to sell guns but allowing customers to purchase every part of a gun to assemble themselves.

CivitAI isn’t the only website that allows the distribution of these models, but it is perhaps the most prominent and credible due to its links in Silicon Valley. Crikey has chosen to name this company due to its existing profile. And it’s obvious that its users are using the platform’s hosted non-explicit models of real people for the purpose of creating explicit imagery.

Skye said she feels violated and annoyed that she has to deal with this. She said she isn’t going to try to get the model taken down because she can’t be bothered. “I hate technology”, she wrote along with two laughing and crying emojis.

But even if Skye wanted to get something like this removed, she would have limited recourse. Image-based abuse has been criminalised in most Australian states and territories according to the Image-Based Abuse Project. But University of Queensland senior research fellow Dr Brendan Walker-Munro, who has written about the threat of generative AI, warns that some of these laws may not apply even in Antonia’s case as they were written with the distribution of real photographic images in mind: “If I made [an image] using AI, it’s not a real picture of that person, so it may not count as image-based abuse.”

However, the federal government’s eSafety commissioner has powers to respond to image-based abuse that would apply in this situation. Under the Online Safety Act, Inman Grant can order the takedown of image-based abuse material even if it is artificially generated. She told Crikey in an email that case-by-case enforcement cannot be relied upon to combat this problem.

“Given the rapid development of these technologies, it’s imperative that providers give careful thought to safety by design, rather than allow further technological evolution to be guided by the outdated ‘move fast and break things’ mantra,” she said.

In Skye’s case, there are even fewer options. Even though the majority of popular models on CivitAI are used to create explicit imagery, there are no public explicit images of Skye so there’s no proof yet that her image has been used in this way.

So what can be done about someone creating a model on a private person’s likeness that may still be embarrassing or hurtful even if it produces non-explicit images? What if an individual or a company is sharing a model and won’t voluntarily take it down when asked? Inman Grant said there’s no enforcement mechanism that her office could use even if it was reported, but said it has released draft regulations that would place obligations on platforms and libraries that could be used to generate seriously harmful material.

Walker-Munro said that while copyright or privacy laws might provide one avenue, the reality is that the law is not keeping up with technological change. He said that most people have already published content featuring their likeness, like holiday photos to Instagram, and that they’re not thinking about how people are already scraping these images to train AI for everything from generative AI models to facial recognition systems.

“While academics, lawyers and government think about these problems, there are already people who are dealing with the consequences every single day,” he said.

Update: This article has been updated to include comment provided by the eSafety commissioner after publication.

So here’s the thing..not only is Australia, the only OECD country, without a Bill of rights, we have no right to privacy.

Also, our image is not copyrighted, unlike the US where there is a personal right established.

There is no general right to privacy in law at all.

The use of AI is ungoverned.

The EU is about to enact AI laws which will prevent this sort of online activity.

In Australia this is all legal..unethical but legal.

similarly your image can be used in advertising without any need for consent or permission.

For any photo, the image taker has the copyright, not the subject.

You image can be taken in a public place and used as long as there is no attempt to identify are imply endorsement.

that has not worked for many Australian celebrities where there likeness has been used to tout products..

A well known gambling company uses a voice actor to imitate a well known comedian..the audio qualities of his voice are not copyrighted and can be exploited without permission or consent.

images from social media are scraped (=stolen) without permission for use anywhere, by anyone.

There is no mechanism in Australia which prevents unfettered use of any online image.

There is an opportunity for improvement…

Given the depths to which extremists have dropped, the impliciations of this tech being widely used during political campaigns is deeply disturbing. Expect there to be widespread releases at crucial times of seemingly credible videos of progressive candidates doing appalling things. Despite their denials, damage will be done. In addition, the credibility of actual footage will be undermined if denied by the target.

It’s going to be a further descent into the cesspit.

There are also services that openly market themselves “clothing removal from an uploaded photo” as a (paid) service.

If somebody can identify who is behind them, there should be amole opportunity to sue them into oblivion, but to my knowledge this hasn’t happened yet.

As for CivitAI, I hope somebody finds away to go after the VCs who fund this, not just the company itself. They have no excuse for not foreseeing that the technology they were funding was going to be abused, but they went ahead and did it anyway because there’s a gold rush on.

Abysmal. thanks for SHARING

It is, as Bingo would say, a real pickle.