It was school funding that started the woes of the Abbott government in 2013. Now, at the end of the parliamentary term, the Turnbull government is still trying to fix the problem created by the fact that voters strongly support the education funding reforms now forever known as the Gonski model, while the Liberal Party has never accepted them, preferring instead to channel Commonwealth funding to private schools.

But because the Coalition doesn’t dare articulate or implement this preference for private schools as a coherent policy — witness the difficulties Malcolm Turnbull created for himself when he pursued the logic of a state income tax to the point of proposing the Commonwealth only fund private schools — it leaves the conservative side at the risk of constant backflipping on funding. The result: the government is now halfway back to where it started from before the 2013 election, but it is billions of dollars shy of the “unity ticket” funding promise that Tony Abbott — desperate to minimise any chance of Kevin Rudd restoring Labor’s electoral fortunes — committed his side to.

It was Christopher Pyne who inflicted the first serious damage on the shiny new Abbott government just weeks after its election in 2013, when he backed away from Abbott’s pre-election commitment to match Labor’s Gonski funding commitments — itself a huge backflip from the Coalition’s initial, hostile reaction to Gonski (or “Conski” as Pyne tried to dub it). Critically, Pyne also wanted to return to the discredited socio-economic status funding model of the Howard years that caused Commonwealth funding for private schools to dramatically increase compared to public school funding. Demonstrating the powerful combination of ineptitude and denialism that would become such a hallmark of the two years of Abbott’s prime ministership, the government then retreated in the face of criticism, committing to funding across the forward estimates, but told the states they would have a free hand with how the spent the money, wouldn’t have to invest their own money and wouldn’t have to comply with the reporting requirements that Labor had insisted on as part of its funding agreements.

Why drop those requirements? They were “Canberra command and control elements,” Pyne said, and it shouldn’t be the job of the Commonwealth to “run public schools out of Canberra”. The problem with ditching those requirements, as Crikey noted at the time, was that there was thus no way to find out if the additional funding was having any impact — indeed, whether it was even being delivered to the disadvantaged students at whom the Gonski funding model was most targeted.

But now the government has reversed itself again. Gone is Pyne’s states’ rights shtick: “Canberra command and control” is back — big time. In order to access the small amount of additional funding the government is stumping up, states will have to comply with a detailed set of rules, including yet more testing for students, staffing requirements and competency-based remuneration models for teachers. Public schools now indeed will be run out of Canberra if states take the money — at least in relation to how they pay teachers and what teachers they hire.

Confused? Join the club.

It gets even more confusing when you realise that better targeting of resources to disadvantaged students is exactly the kind of investment that a country aiming to be “agile” and “innovative”, one hoping to encourage its people to be more skilled and flexible in an era of rapid technological change and emerging commercial opportunities, should be making. Unless your idea of “innovation” comes with Old School Tie links for your start-up and a sandstone university pedigree.

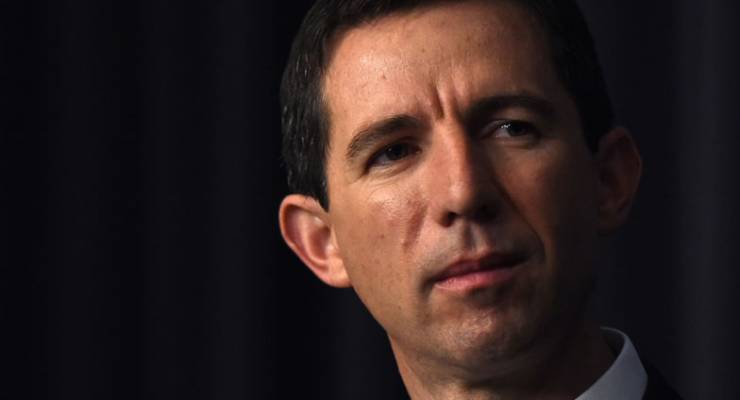

The other backflip of yesterday, of course, is on funding itself. For months, the official line from current Education Minister Simon Birmingham has been that simply providing more funding for education wasn’t the answer. “Spending more does not automatically equal better outcomes,” he said in March to a non-government school conference. “We do need to shift the education debate away from one that is dominated by inputs like funding.” Yesterday’s announcement confirms the failure of the government to achieve that — and it was never likely to do so while it had the twin challenges of having so publicly walked away from Gonski and the 2014-15 budget cuts to health and education that had even Coalition premiers and education ministers froth-mouthed with rage.

So now, the government has lifted indexation of schools funding from the absurdly low level it was set at by Abbott and Hockey (CPI, or around 2.5% pa) to 3.6% — an increase that’s still only halfway to the 4.7% indexation promised by the Gillard government. In the 2014-14 budget, the government patted itself on the back for the 2.5% indexation as “sensible indexation arrangements for schools”, but it’s marvelous how political necessity can transform “sensible” into, by the government’s own lights, less than 70% of what are now dubbed “real education costs”.

To properly nullify Labor’s attack on education funding, the Coalition will need to go for the other half of the increase. It won’t do it, not because it hasn’t got the money — it magically has tens of billions of dollars for extra defence spending between now and 2025, entirely unfunded — but because it has never accepted the rationale for the Gonski funding reforms. Halfway there, livin’ on a prayer — the prayer that voters accept that half a Gonski is good enough.

Abbott had so much help at looking inept – Pyne not least.

As for the “New Turnbull” model – a lead crow-bar – looks the part and feels it – until it’s used?

Yes, you are confused Bernard.

The States’ declining the opportunity to levy income tax has given the Turnbull government much more authority in the matter of funding social services. Turnbull can say, “The States just want to spend and it is left to us to constrain that spending to what the country can afford”. The education funding is clearly an election bribe to blunt Shorten’s “fairness” campaign and calling it a backflip is a bit more lefty campaigning. Did you say that Shorten made a backflip when he announced changes to negative gearing? I must check back on your articles around that time to find out.

Your reference to the submarine contract displays the hipster lefty fashion for having not army, navy or air force. Letters to the editor of lefty journals like Fairfax are full of people complaining about the hospitals that could be funded by not buying the subs. There was even a cartoon of a sub portioned into social spending initiatives such as hospitals and schools, the NDIS and pensions. It’s juvenile. It’s why the left is rapidly becoming such an unelectable fringe group.

“All we are saaaayinnng, is give peace a chance”

The question is, do we need 12 submarines? Perhaps 6 will do?

Do we need to spend billions on the JSF/F-35? Could we do with a cheaper alternative without all the bells and whistles?

Allowing the states to levy income tax may make sense to those in Canberra, so they can offload their responsibilities.

A better way would be for the feds to directly fund schools (public) and hospitals. They can cut out 7 bureaucracies for each service.

In terms of trying to save money, they could probably have saved quite a bit by fully importing the subs.

What a hilariously partisan comment. Nobody bought Turnbull’s line immediately after the states rejected the states’ income tax proposal, why would anyone buy that now? It’s such a crap argument anyway, “we gave them the opportunity to raise their own taxes, that we don’t have the guts to do, so now they can go and jump!” It’s laughable.

And while hoisting the straw man of the left who want know army, navy or air force, you then cut him down. Well done, however the vast majority of people who are left leaning voters already accept the need for armed services, that isn’t even a debate. Those people are fringes of the fringe, not representative of the left at all.

And all the while, the very heart of the LNP is disintegrating up their own fundament(al) lack of a cohesive reason for being.

Education will trick this government up badly, because there is a mini baby boom at the moment, and all of those kids have two voting parents. It’s a bad look for the LNP, particularly because everyone knows that they think public schools should be under-funded, because that’s what the plebs deserve.

Howard’s socio-economic status based funding, it was a lie then, and just another ‘reform’ from the Howard years that has to be undone. Only the GST will remain as evidence that Howard and Costello ever existed.

OneHand = NoShame. Does not your conscience even occasionally twinge? Just a little?

It is a continuing foolish belief of people who hold so called progressive views that they are somehow morally correct and that those who hold alternative views are evil. Hence your appeal to my conscience AR. You believe I am morally wrong. Such a view makes the battle of ideas almost impossible to have. It’s why doctrinaire left wing parties are unelectable. British Labor is a great example. Corbyn is not interested in actually winning an election. Someone has to make adult decisions about Australia’s defence strategy and it is clearly not going to come from the progressive left.

OneHand – it is not your, apparent, beliefs & opinions that I find (most) objectionable but the mendacious and tendentious way that you try to derail any thread threatening to your paymasters by obfuscation, misdirection and irrelevancies.

And did I mention the plain, simple misstatements of fact – aka B/S?

“Which Limited News Party will you be voting for?”

“all we are saying is give peace a chance” …yeah, no appeal in that slogan to a rabid rightard. Too many words for a start. The right of politics prefers something brief , like… “fight the good fight”, ” the injuns are comin” , “shock and awe” , “us and them” … that kind of stuff.