The man who blew the whistle 20 years ago gives an inside account on Morrison’s modus operandi.

Scott Morrison might have allegedly bullied Christine Holgate out of her Australia Post job, publicly humiliated her, and cut across the lines of independence designed to protect government enterprises from political interference… but it was far from the first time for him.

Indeed, Morrison’s behaviour has strong echoes with his role in a political furore which, though little known in Australia, played out dramatically in New Zealand more than 20 years ago.

Dr Gerry McSweeny was a firsthand witness to the shenanigans known as the “tourist wars” and remembers well the role Morrison played as the director of a new government tourism agency.

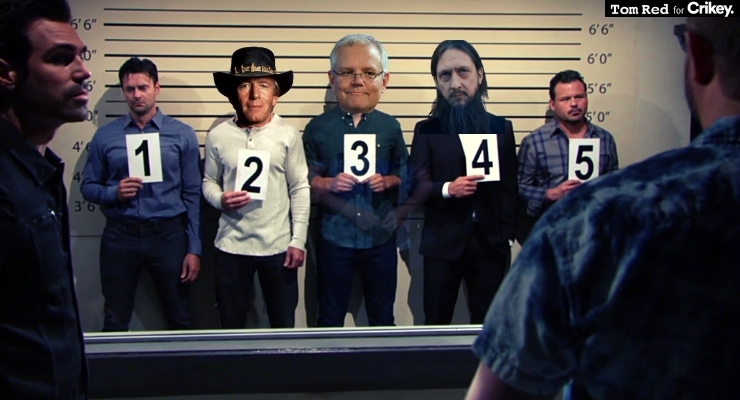

“He has a disrespect for process, for parliament and for independence,” McSweeney told Inq. “There’s a pattern there of bulldozing ahead despite the constitutional barriers.”

Former political journalist Nick Venter had a more colourful turn of phrase. He likened Morrison’s actions to “a cross between Rasputin and Crocodile Dundee”.

“Here he is, whispering into the minister’s ear about the board,” wrote Venter. “There he is, crashing through the undergrowth without regard for reputation or bureaucratic convention.”

The board? The minister? The story that unfolded in 1998 in NZ bears an uncanny similarity to Canberra’s very own Holgate affair.

Morrison had been brought over from Australia as a 30-year-old hot shot to run the Office of Tourism and Sport, a creation of the conservative National Party government.

Within weeks Morrison had left an indelible mark. The tourism board’s three most senior figures — the chair, the deputy chair and the chief executive — were gone. They were paid out a total of close to NZ$1 million (A$925,000), a huge sum at the time, all of it taxpayers’ money and a far cry from the paltry A$20,000 cost of Holgate’s four Cartier watches. The payments were kept secret. Elements of the payouts were later ruled unlawful.

Gerry McSweeney was a member of the board. As he watched the mayhem unfold, he was appalled.

“I suspect it was just about power,” McSweeney told Inq. “You had the meeting of two people [Morrison and Tourism Minister Mike McCully] who were very ambitious.

“Morrison hid behind the minister’s office. He made the bullets and McCully fired them. The aim was to replace them [the sacked board members] with people friendly to the government.”

McSweeney later resigned, having concluded that the government had no interest in an independent board.

“It made a mockery of the so-called independence of the board,” McSweeney said, adding that independence was seen not as sacrosanct but as “an impediment”.

While sitting on the board, McSweeney quietly turned whistleblower. He passed on information to a journalist whose national newspaper reports led to a special investigation by the New Zealand auditor-general.

Completed 20 years ago, the auditor-general’s report shows a now familiar modus operandi.

Using consultants

As director of the agency Morrison commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to conduct a “management review” of the board to be undertaken “quietly and discreetly”. The auditor-general later found that Morrison alone had access to the report as it was being prepared and had made “written and oral” comments on it.

“It is apparent that these comments influenced the shape of the report,” the AG found.

Controlling the process

Morrison had ordered that PwC make no contact with the minister, the minister’s office or individual members of the board. This meant no one had a chance to defend themselves as the report was being prepared, even though the report was ultimately critical of the board and the members “in a number of respects”.

PwC told the auditor-general that they were uncomfortable with — but did not object to — the restrictions placed by Morrison. They later conceded to the AG that “what occurred was not acceptable practise for a firm of management consultants”.

Sacking ultimatum not justifiable

In his covering letter to the tourism minister, Morrison described the shortcomings which the report had found as “extremely serious”. He encouraged the minister to take “direct and immediate action” to rectify them. He recommended that the minister give the board chairperson seven days to come up with a satisfactory explanation as to why he should continue in the job or be dismissed.

“We were surprised by the vehemence and timing of this advice,” the auditor-general commented. “Mr Morrison was aware that the board’s directors (including the chairperson) had deliberately been excluded from the review process, as part of the terms of reference.”

The PwC consultant had also told the AG that in his view the report did not justify moving on the chairperson the way Morrison had recommended.

Separately, the AG found that “despite Mr Morrison’s advice to the minister, we have seen no evidence which would have justified the minister terminating the appointments” of the two board members.

Misrepresenting the true position

When the PwC report was eventually seen by the board staff from whom information had been sought, they were “unanimous” that their views had been “misrepresented”. Board members felt “justifiably aggrieved”, according to the AG, that their performance had been criticised “without foundation or an opportunity to comment”.

“When it turned out that the report was to be used by the minister as a basis for considering their removal from office, they came understandably to the view that the process had been ‘hijacked’.”

Claims of constructive dismissal

The auditor-general’s report canvassed the idea that the board members who resigned might be able to claim “constructive dismissal” given the minister, by his actions, had made life “untenable” for board members.

There are parallels with the case of Christine Holgate, who employment specialists consider might have a constructive dismissal case — despite her resignation letter — given the public pressure heaped on her by Morrison. On the question of whether or not Holgate should step aside during an investigation, Morrison had loudly proclaimed: “If she doesn’t wish to do that, she can go.”

Twenty-two years on, Gerry McSweeney has been made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit — the country’s highest civilian honour — for his lifelong service to conservation and the environment. From the wilderness lodge he runs at Lake Moeraki on New Zealand’s south island — a place where you can see the Fiordland crested penguin — his final assessment was that Morrison “would have seen sacrificial lambs in the leadership”.

“Picking off soft targets,” he added, “seems to have been a career projection of your PM.”

Inq asked the Prime Minister’s Office for comment.

What do you think of Scott Morrison’s behaviour, both now and in the past? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say section.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.