The Lady Fitzherbert docked in Sydney on 26 September, 1838. After a four-month journey, my great, great grandfather John Fairfax, his wife Sarah and four children — one of whom had been born during the voyage and who was to die two months after arrival — started their new life. John had been bankrupted in England fighting a defamation action that he won.

Imagine Sarah as John Fitzgerald Fairfax did in his 1941 biography: “If her heart was cold with fear, her face was serene with courage.”

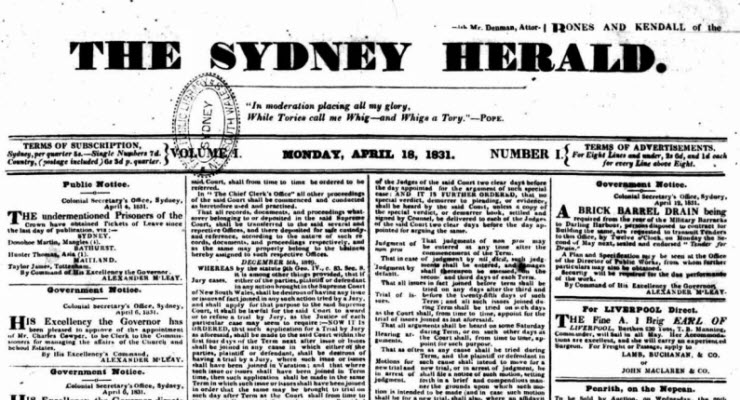

After a period as the librarian of the Australian Subscription Library — the precursor of today’s State Library of NSW — John teamed up with Charles Kemp to buy the Sydney Herald in 1841 for £10,000. Now, 180 years later and 190 years since its first publication, the paper survives as The Sydney Morning Herald.

Today the Herald is dominated by an entertainment company once owned by the Fairfax family’s arch media rival, the Packer family, former publishers of The Daily Telegraph. The Fairfax family’s extensive involvement with the paper effectively concluded in 1987 through the actions of one of their own, Warwick Fairfax. His audacious bid for the entire company ended in failure.

But despite a series of ownership changes, the Herald remains to tell stories, break news and act as an investigative watchdog over our citizens, corporates and politicians.

The paper has produced and employed many excellent journalists and editors. Much can be said about the history of the people and indeed the events they reported. The Fairfax family rarely interposed themselves in editorial matters, although occasionally this was necessary on major issues such as elections and, perhaps, sensitive stories.

On one occasion of relatively minor importance, the chairman Sir Warwick Fairfax wrote to then-editor John Pringle, complaining about the cartoonist, Emeric, and his depiction of a person “with severed hands and limbs”.

Fairfax said: “I see nothing funny in this. On the contrary it strikes me as being macabre, ghoulish and rather unpleasant”.

Pringle, as is the wont of editors, replied: “Emeric’s severed hands and legs are certainly a common feature in his cartoons. I find them amusing and distinctive, though I can see your point. I will talk to Emeric and see if he can reduce the number of limbs…”

Advertisements appeared on the front page of the paper until 1944. News, which had originally only arrived by sea, was adapting to modern means of communication and was therefore seen as more important, relegating advertisements to the later pages. The bulk of these were classified advertisements. These “rivers of gold” were to become the fulcrum upon which the company thrived, and the envy of its competitors. They were a major feature on Saturdays when, especially during the 1970s and 1980s, the paper frequently exceeded 300 broadsheet pages.

Journalists wrote anonymously until about 1960 when bylines were introduced to satisfy the ever-present journalistic egos. One of the best-known journalists, T.M. (Tom) Fitzgerald, never wrote under a byline — merely “finance editor” — although his writing and news breaking was so profound everyone knew who he was.

When I broke two front-page stories for the Herald while working in London, I was simply “our London correspondent”!

“Column 8”, occupying the last or eighth column of the front page, was introduced in 1947 headed by the logo of an elderly bonneted lady with a knitting needle. Her influence and the column were so great that the paper itself became known affectionately as “Granny”.

The first item in the first column on Saturday January 11, 1947 was:

VALUES. Don Bradman, Test cricketer, can’t remember the number of autographs he’s signed — “must run into many thousands”. Marcus Oliphant, atom expert, can. He’s never been asked for one.

In recent years the column disappeared temporarily, only to be reinstated after howls of protest. Although no longer on page one in Column 8 position, Granny’s image has recently been given a COVID mask!

After the 1987 takeover action of young Warwick, the paper lost its “proprietorial” direction. It was subjected to chairmen and chief executive officers, many of whom regarded their positions as a top rung on the business and social ladders. But one thing remained: the organisation retained its authority and pre-eminence for independent journalism.

Of course not everyone concurred with its views or its treatment of news, but the Herald did not survive for 190 years without being a trusted news source.

It is worth reminding ourselves of the words in the first edition published on Monday April 18, 1831:

Our editorial management shall be conducted upon principles of candour, honesty, and honour. Respect and deference shall be paid to all classes. Freedom of thinking and speaking shall be conceded, and demanded. We have no wish to mislead; no interests to gratify by unsparing abuse, or indiscriminate approbation. We shall regret opposition, when we could wish to concur, and bestow the meed of praise. We shall dissent with respect, and reason with a desire, not to gain a point, but to establish a principle. By these sentiments we shall be guided, and, whether friends or foes, by these we shall judge others; we have a right, therefore, to expect that by these we shall be judged.

I am deeply gratified by my family’s association with the Herald over five generations and the principles it upheld.

This article first appeared in the newsletter of the Union, University and Schools Club of Sydney.

John B Fairfax AO was inducted into the Australian Media Hall of Fame in 2018. Fairfax is also an investor in Private Media, the publisher of Crikey.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.