There is something grimly hilarious about the communiques from Sydney these days. As Melbourne soldiers through its fifth lockdown with a grim determination, and the case numbers reliably fall day by day in the exact proportion expected, Sydney seems to be debating how many people can go to a real estate showing or how long the queue is in something called a Bing Lee.

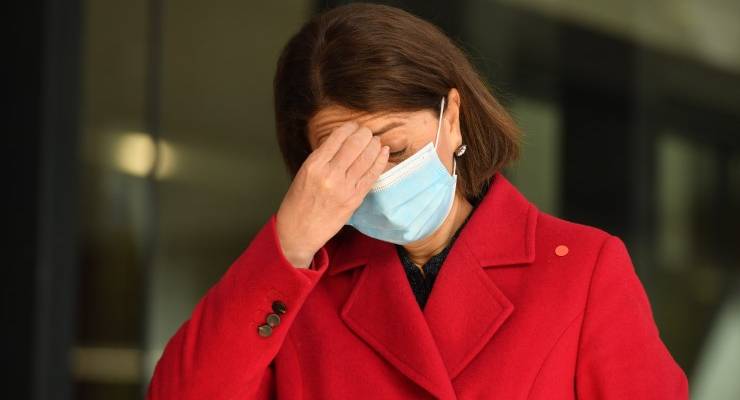

Gladys, the leader of the “best government in Australia” looks hapless, panicked, and entirely out of her depth. The entire government is leaderless and directionless. A severe lockdown of four weeks would have knocked this on the head (Victorians are expert epidemiologists by now). Instead, it will drag on and on in a half-arsed fashion, the state never getting on top of it.

The question is, does this mark a particular failure by the Berejiklian government? Or is it a more general divide in Australian culture, particularly between Melbourne and Sydney? And what does this mean for the actual federation?

The government screw-up angle is attractive, of course. After all, this is a government that couldn’t even get the gauges on its new tram system to match up. But it may be that the problems go deeper.

Gladys appears to have gone for an ineffectual lockdown mainly because her government is a client of the big retailers. But also because she has a sneaking suspicion that a total lockdown simply may not be enforceable in Sydney. So many people would flaunt it that the government’s authority would be undermined from the start. Alternatively, repression would have to be at a new level — a Rum Corps with tasers sort of thing.

This points to a major problem, and a very interesting one for Australia. As Melbourne and Adelaide complete their lockdowns in an observant manner — with a congruence between government demands and a rational understanding of the situation — Sydney is a madhouse. Queensland would most likely be the same, except even a virus finds Brisbane too ugly to spend too much time in.

We have become two nations, roughly north and south, with two substantially different approaches to the world. It’s like Germany and Italy, but with the polarities reversed, the federation line simply shadowing the boundaries of a much greater division.

How did this come about? To a degree it has been produced relatively recently, by a sort of deliberate branding. Sydney divested itself of residual British trappings in the 1960s and became, as Mort Sahl called it, “a rehearsal for Los Angeles”. In the 1980s, when Australia became the global flavour of the month, it was the outback and Sydney — the Opera House, Crocodile Dundee, Olivia Newton-John, Ken Done and their ilk — that was Australia.

Melbourne became like itself, only more so — the world’s first emo city. The Cain government was in some ways a continuation of the social liberalism of the Hamer government, and after an eight year interregnum, Labor was returned to power. The Andrews government is, in many respects, well to the right of Hamer, but the notion that freedom and flourishing come through universal enablement is well embedded.

The deep cause of this is often taken to be the division between convict cities and free ones (Melbourne had some convicts, but very few). Sydney was an authoritarian state before it was a society; the state presented itself as something necessary, but inimical to human freedom. In Melbourne and Adelaide, the violent capricious state was turned outwards onto the Indigenous, by that very means establishing a degree of shared consensus among whites. The state was cosa nostra — our thing.

That might have faded but then a bloke arrived in Sydney who would set it all in stone. John Anderson took up the chair of philosophy in 1927. He was a Stalinist, then a Trotskyist; by the late 1930s he was a libertarian anarchist. “It is always wrong to call the police, but it is sometimes necessary,” he remarked, which could serve as a summary of his philosophy — and of Gladys’s haphazard lockdown strategy.

Anderson’s students became “The Push”, and The Push became the anti-communist right and the Liberal Party (Crazy James McAuley and Peter “Pickled” Coleman) and the libertarian left (hahaha Paddy McGuinness, Germaine Greer, Margaret Fink, Frank Moorhouse, Nevilles Richard and Jill, Robert Hughes and so on). Sydney’s Marxists were Stalinists who shared the Push’s anti-statism (it’s complicated); Melbourne’s (non-Catholic) right were social liberals, its Marxists those who take six months to define “state” before trying to take it over.

These differences shaped politics and society to some degree for two generations, though contained within a greater Australian commonality. They have burst out now because the conditions we live under — a virus that is becoming a threat to the capacity to carry on common life, without abandoning the vulnerable to their fate — have pushed the difference to an existential level.

Long answer short: Melbourne wins the argument (Adelaide too, but I think of it as a mock-Tudor English village filled with serial killers, rather than a city). Freedom and flourishing come from positive freedom — the capacity for universal safety and possibility, acquired through curbs on the individual — rather than “negative” liberty, the right of the individual to pretend that they do not impinge on another unless they do so visibly and physically.

Out of this crisis has come a supreme crisis of federalism. Central authority cannot be ceded to, both structurally and because it has been abdicated by the incumbent; but nor can differences now be respected within a whole. This isn’t “potato scallops” v “potato cakes” we’re talking about. This is life and death.

Sovereignty, moral and actual, resides with the states. For Victoria and others, total borders and punishment for their transgression should be enforced for a period longer, to protect the freedoms we have gained at harsh cost. This is preferable to having to extend our restrictions in an act of inadvertent federation solidarity.

And the example of our success may up the pressure on Gladys to have a genuine lockdown. Even as the communiques from the plague lands tell of descent into cannibalism and — nooooooooo! — falling house prices.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.