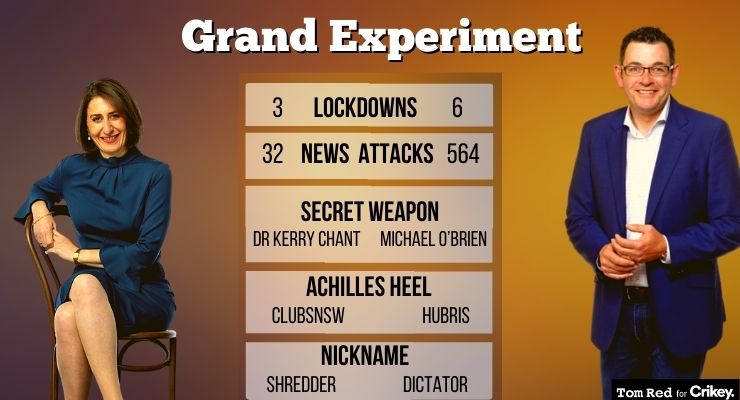

The federal government’s embrace of “early interventions, short, sharp lockdowns” as the most effective response to outbreaks of COVID was more than just hypocrisy, given its earlier attacks on the Andrews and McGowan governments. It was also the conclusion of a large-scale experiment in responding to a pandemic.

The experiment has been conducted with two different approaches, which might be described as “interventionist” and “market-based”. As the names suggest, they reflect different ideologies and different political mindsets.

The interventionist approach, exemplified best by the Andrews government in Victoria, relies heavily on locking down communities, suspending a lot of ordinary economic activities and providing government support for those affected until case numbers are low enough to safely reopen. It also relies on closed borders and tight quarantine requirements for the small number of people allowed into the country.

The market-based approach prefers to avoid lockdown, adopting a technocratic approach in which contact tracing, using data acquired mainly from apps, is the primary means of keeping on top of COVID, while people are allowed, with certain restrictions, to continue their normal economic activities and move about. Income support is regarded as unnecessary. Adherents of the market-based approach are also uncomfortable with closed borders and would like to see more people enter the country.

You can mix and match some of these elements, of course: the Morrison government, until recently, has been a strong supporter of the market-based approach but was responsible for the most stringent border closure of all — despite helping Clive Palmer challenge Western Australia’s border restrictions and even now criticising Premier Mark McGowan for his resistance to allowing easterners to enter his state.

When Josh Frydenberg produced Treasury modelling to back up his changed view that “early interventions, short, sharp lockdowns” were the best way to address outbreaks in economic terms, it was somewhat superfluous: the Berejiklian government in NSW has been giving us a real-time demonstration of how the market-based approach cost far more than the interventionist approach.

Not merely did her pro-business “lockdown lite” initial approach — influenced by the views of her party’s business base — fail catastrophically in terms of preventing a Sydney outbreak, it enabled the spread of the virus beyond Sydney to the rest of NSW, and thence to Victoria and the ACT.

Sydney now looks set to stay locked down well into September, inflicting a massive blow on employment and economic growth on its own, and risking further economic damage courtesy of the spread to other states and territories. The market-based approach has delivered the worst possible outcome for markets — an irony presumably lost on business figures and their media supporters who continue to complain about lockdowns and closed borders.

It’s of a piece with one of the broader characteristics of the last 18 months — how bit by bit the core beliefs of neoliberalism have proved at best wholly inadequate and often downright harmful.

The government’s rejection of deficit hysteria and embrace of massive fiscal stimulus supported a rapid recovery (and delivered windfall profits to the bottom lines of many corporations). Closed borders and the abatement of a steady flow of temporary workers helped unemployment recover quickly. The Reserve Bank abandoned its obsessive focus on expected inflation and made higher wages growth a central policy objective. Effective lockdowns proved the key to rapid recovery — until a market-based approach derailed everything in eastern Australia.

The question then is whether governments and business will understand the lessons from the grand experiment, or simply revert to status quo ante economic thinking about the need for governments to curl up into as tiny a ball as possible and let markets get on with maximising individual freedom and personal welfare, and skewing policy towards the demands of business.

In particular, will it inform the decisions of the NSW and federal governments in coming months as they feel the temptation to declare victory over COVID once vaccination reaches 80% and decide that lockdowns and other restrictions are no longer needed?

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.