Note: this article discusses child sexual abuse.

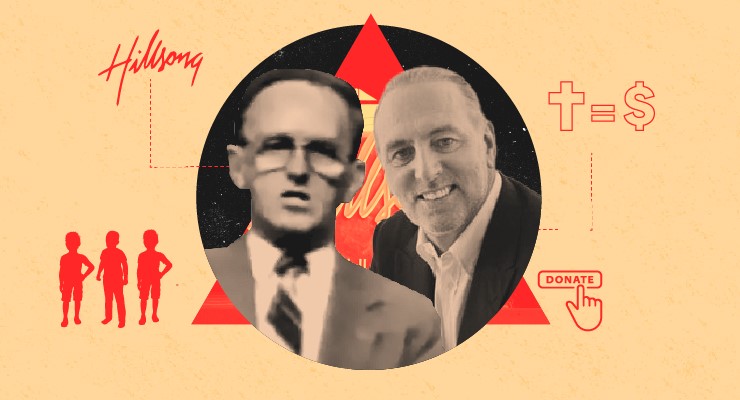

The charge of concealment laid this month against Hillsong Pastor Brian Houston is momentous, whether or not Houston is ultimately found guilty.

The criminal charge relates to events more than two decades ago, when Houston failed to notify police when he allegedly became aware that his father, the late pastor Frank Houston, had sexually abused a young boy. The decision to charge Brian Houston was signed off by the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP).

Houston will return to Australia from the United States for a magistrates court hearing in Sydney in October where, he has said, he will vigorously defend the charge. Houston and Hillsong have expressed disappointment with the action, saying they have been transparent about the events of the day.

The stakes are high. In the pantheon of Australian religious leaders Houston is a major figure — and not just because of his closeness to Prime Minister Scott Morrison.

If found guilty the consequences would be immense. The massive Hillsong enterprise, locally and globally, is built entirely around him and his wife, Bobbie. Hillsong is Houston in a way that doesn’t feature in other churches.

Then there’s the threat it poses to the corporate behemoth that the church has become. Houston is a director of a maze of Hillsong enterprises. There are 19 Hillsong entities registered with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission (ACNC), where they enjoy a variety of tax breaks.

Under the Corporations Act you cannot be a company director if you are convicted of an offence that involves dishonesty and is punishable by at least three months’ jail.

The crime of concealment carries a potential five-year sentence, depending on the seriousness of the abuse that was concealed. Does it add up to dishonesty under the Corporations Act to conceal information from the police? That might be up for debate.

Oddly, the charities commission has no power to remove a “responsible person” from a class of religious charities known as “basic religious charities”. Houston has been a “responsible person” on several of these, notwithstanding the McClellan royal commission into child sex abuse which concluded he had failed to pass on information about his father’s crimes to police.

High stakes for prosecutors

Crikey legal expert Michael Bradley says that because the crime of concealment (under section 316A of the NSW Crimes Act) has many elements, it is hard to prove.

“Strong evidence of what the accused knew, the information or evidence they held, or what they should have known if they’d put their mind to it, is a prerequisite,” Bradley wrote.

Added to this is that the law provides a “reasonable excuse” to not pass on information to police if the victim is an adult at the time the information becomes known, and that victim does not want the police involved.

That’s how the law stands under an amendment in 2018. In 1999 the law said merely that it was possible to have a “reasonable excuse” without giving specific reasons.

Hillsong and Houston have always offered this as the reason for not reporting Frank Houston to the police. They may be able to argue that the Parliament has now clarified the intention.

The charges Houston faces are very different from those which led to the now-overturned conviction of Cardinal George Pell. But the lengthy legal process — going through the magistrates court and the County Court to the Court of Criminal Appeal which ultimately culminated in Pell’s successful appeal to the High Court — is a pointer to how hard the charges might be fought, and the pressure that may come upon the police and the DPP.

Scott Morrison as collateral damage?

The odd symmetry is that both Houston and Pell are, or have been, confidantes of sitting prime ministers. Tony Abbott remained an admirer of Pell, despite findings on his conduct from the McClellan royal commission into child abuse. And Scott Morrison’s association with Houston goes back more than 20 years.

Morrison acknowledged Houston in his first speech to Parliament in 2007. He attempted to have Houston invited to a 2019 White House dinner hosted by then US president Donald Trump — and then dissembled when word got out. He singled Houston out while speaking on stage at the Conference of Australian Christian Churches in April. He has, in short, put a lot on the line for Brian Houston.

Why recite this history? Whatever the result of the legal action against Houston, there is a powerful moral case for Houston and Hillsong to answer, stretching back to the days of Frank Houston’s offending as a serial child sex abuser in his home country of New Zealand. As part one of Crikey’s investigation shows, Frank Houston has bequeathed a legacy of enormous suffering by an untold number of victims dating back to the 1940s.

There is no legal obligation for Hillsong or Houston to recompense Frank Houston’s New Zealand victims. Frank Houston is long dead. It may be, though, that Morrison is not aware in any detail of the crimes of the great evangelist Frank Houston, and the subsequent moral failure of Hillsong — and, arguably, senior officials of the Pentecostal movement in Australia.

Perhaps he should take time to become aware before he next takes the stage at a Pentecostal event and, by his very presence, gives prime ministerial endorsement to men who still have questions to answer about the past.

Read part one: The legal case against Brian Houston pales in comparison to the church’s moral failure.

Survivors of abuse can find support by calling Bravehearts at 1800 272 831 or the Blue Knot Foundation at 1300 657 380. The Kids Helpline is 1800 55 1800. Further support is available at Lifeline is on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue is 1300 22 4636.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.