The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has released its third report in its sixth assessment series on the status of climate change science, impacts and mitigation. It found that even if all policies announced by governments across the world were fully implemented, the earth would still warmer by 3.2℃ degrees by 2100.

The science suggests warming to this extent would see unprecedented weather events and water shortages causing devastation. In some of the strongest wording used to date, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said: “Some government and business leaders are saying one thing but doing another. Simply put, they are lying. And the results will be catastrophic.”

These findings add to the mounting evidence the IPCC has compiled over the past three decades, and the urgency grows with the release of each report. But what is Australia’s record of responding to climate science? Crikey looks back on its response to successive reports.

First assessment report

The newly established IPCC released its first assessment report in 1990. It confirmed that the natural greenhouse effect was warming the earth, and human activities were contributing to the increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases. It also endorsed the “Toronto targets”, which aimed for a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2005 at 1988 levels.

After initially rejecting the target, Australia signed up to the 20% reduction goal in 1990, and named it an “interim planning target”. The commitment was heavily caveated by the “no regrets” strategy that requires that any action taken would not be at the expense of the economy.

As a result of the first report, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) became the first climate treaty, which Australia ratified in 1992.

Second assessment report

In December 1995 the IPCC released its second report, which found “a discernible human influence on global climate”. The newly elected Howard government committed to the UNFCC’s “activities implemented jointly” project, in which nations cooperate on emissions reduction projects. Then environment minister Robert Hill explained that “in the long term [Australia] would be seeking credit from the international community for our efforts”.

Ahead of the Kyoto climate summit in 1997, Hill said: “The adoption of a uniform reduction target at the upcoming Kyoto conference would have a devastating impact on Australian industry and its ability to create jobs.” Australia signed but did not ratify the Kyoto agreement, making the commitment legally non-binding.

Third assessment report

The next IPCC report, in 2001, established the growing scientific evidence of global temperature increase across the 20th century. The report predicted temperatures will increase by 1.4-5.8 degrees across the 21st century.

Australia legislated conservative renewable energy targets, but the government rejected criticisms of its climate policy in a report tabled by the Senate standing committee on the environment. The report is titled “The Heat is On: Australia’s Greenhouse Future” and makes more than 100 recommendations.

Australia continues to refuse to sign the Kyoto Protocol.

Fourth assessment report

In early 2007, the newest IPCC report affirmed that increases in global temperature were driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gases — with 90% certainty. At the same time, Australia’s climate policy was focused on a potential emissions trading scheme. Despite tabling the proposal years earlier, the Howard government makes an election promise to introduce an emissions trading scheme.

The newly elected Rudd government ratified the Kyoto Protocol. The 2009-10 budget included significant climate policy, with new targets and a carbon pollution reduction scheme (CPRS). The legislation of the CPRS failed to pass the Senate, while carbon pricing was eventually implemented.

Fifth assessment report

The IPCC released its biggest report yet, published in multiple stages across 2013-14. It continued to crystallise the risk climate change posed to human health, national security and agriculture, and further evidence of human impact on climate change.

The newly elected Abbott government wound back much of the existing climate policy, and after multiple attempts, carbon pricing mechanisms were repealed. Australia became the first country to reverse policy designed to take action on climate change. In the following years, climate policy continued to be a highly politicised issue, with limited action taken at the federal level.

Sixth assessment report

The IPCC’s most comprehensive report on climate change is released across 2021 and 2022, with the final part released yesterday detailing what mitigation is possible. It describes the chances of mitigation as a “now or never” situation, with the original goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees essentially impossible.

Australia has committed to net zero emissions by 2050, but the more aggressive targets the IPCC reports demand are lacking.

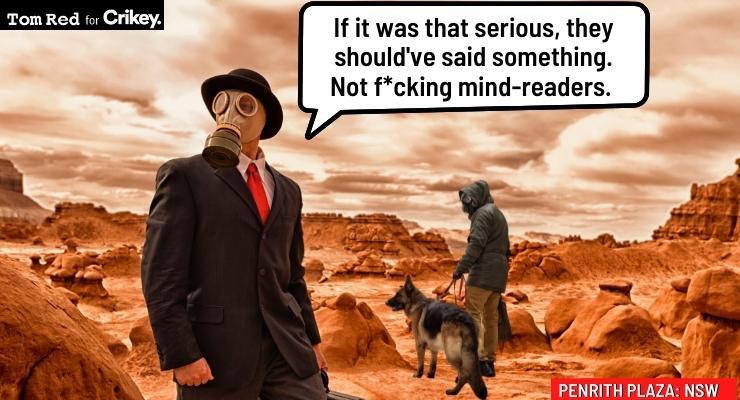

In the first government response to the latest report, Assistant Energy Minister Tim Wilson told RN Breakfast today that the government was exceeding its interim target of 26-28% emissions reductions by 2030, and diverted attention to other countries who Wilson claimed need “to follow our lead”. He pointed to the UK that is “backsliding on their commitments” and China who “hasn’t even committed to net zero”.

This comes after the Coalition government’s 2021-22 budget was criticised for failing to take further action on climate change.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.